The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Hereās the last time I remember playing with my childhood imaginary friend, Mister Rice Guy. Iām 8, and itās my least favorite time of day: recess. Iām friendless and alone at my new school, and so I bring him with me that day ā normally he stays home. We walk the perimeter of the chain-link enclosed yard behind the school as kids around us scream and play. My classmates assume Iām talking to myself, so they start mouthing my words, wreathing them with derisive laughter.

Until that day, my imaginary friend had been a source of comfort. That moment transformed him into a source of shame. Mister Rice Guy (whose name I am sure I took from misunderstanding the phrase āMister Nice Guyā) disappeared.

Thirty-two years later, in the nadir of a global pandemic, he came back again. But more on that in a moment.

According to my parents, Mister Rice Guy first showed up when I was 5. I was an awkward only child with a need for an imaginary companion who understood me. I was very private about him. He never came to the dinner table, and I never told my parents what he looked like. He and I spent long hours locked in conversation, playing together on the floor of my green-carpeted bedroom. What did he look like? In later years, Iāve been embarrassed to admit I couldnāt quite remember. What I do know is how he made me feel. Safe and warm. Seen, heard and protected.

Maybe you had a special friend in childhood who made you feel that way. Or more than one. The experience exists on a spectrum, stretching from conversations with a favorite toy or stuffed animal to personified imaginary entities like mine.

For the most part, children know these friends are āpretend.ā Thatās the point. Theyāre not a delusion, but rather a way to access feelings and qualities that our youthful selves know to be important, but which weāre not ready to claim as part of our essential identities. Theyāre our emotional backpacks, apart but close at hand, there when needed to deliver a store of strength or calm.

Experts say a childās imaginary friend can be someone to consult when making a decision. They can make us feel better about our peer relationships, giving us insights on how to handle friendships and disagreements. And they offer the capacity to imagine new outcomes to difficult situations. Feeling trapped and confused, say, in a pandemic? Your imaginary friend might help you imagine a way out.

āThe kind of mind that can reason about the past and think about the future is the kind of mind that can come up with an alternative,ā says Marjorie Taylor, a professor emerita of psychology at the University of Oregon. Taylor has studied childrenās fantasy lives for decades. I called her up recently to ask if I was crazy, because suddenly Mister Rice Guy was back.

No, she said. I was not crazy. In fact, more adults could benefit from finding new ways to play.

In the shortest, darkest days of that first fearful winter, as COVID-19 mutations circled the globe, I sat at home, hushed and frightened and uncertain. From bleary days to long, insomniac nights, a heaviness assailed me in my solar plexus. It dragged me down and made me cry, on and off, for days at a time. And then suddenly, one night, all I could think of was Mister Rice Guy. I swore I could feel his presence in my bedroom.

Was I losing my mind? I looked around in the dark and felt like a fool. Why would my old companion be back in my life? Could he even recognize this sad, 40-year-old variation on the (also kind of sad) child he had comforted at the age of 8?

The next morning, I woke up, exhausted and confused, and took a hike for the first time in months. I drove to a hilly park with fresh green grass. At the outset, I wondered if Mister Rice Guy would tag along, but still it made no sense. Why would my old companion want a friend like me? I was weepy and depressed and old. If he were there, heād want to play.

Suddenly I knew what I needed to do. I took off my pack, climbed a medium-size hill, waited until no one else was looking ā and rolled down that hill. I collapsed at the bottom, giggly and dizzy and covered in burs. You cannot be sad after you roll down a hill. And I know for a fact that I didnāt roll down that hill all by myself. I got a push from Mister Rice Guy.

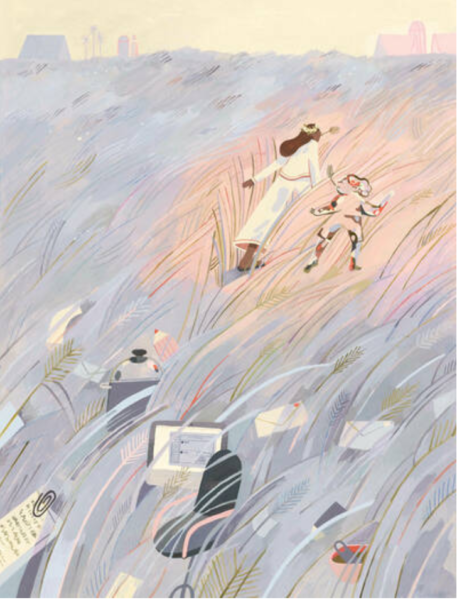

After that, we spent a lot of time together. As the first pandemic winter yielded to its second spring, I left my apartment as often as I could, taking long walks where I paid special attention to bird and insect worlds. What were their days like? I imagined walking side by side with Mister Rice Guy on these explorations, which made them feel adventurous and fun. That line of ants streaming by a smeared banana ā where was their nest? (We tried to follow the trail of ants for as far as we could.) How closely could we sneak up next to the hummingbirds on my street before they zoomed away? By then Iād realized, to my delight, that I hadnāt forgotten what my childhood friend looked like: He looked like no one, or like everyone who isnāt me. In an era that seems all too ready to demonize the Other, here was a presence of pure Otherness, radiating the acceptance I hadnāt been able to access on my own.

If someone saw me talking to myself, let them wonder. I felt no shame.

Iām sure I am not alone in having invoked a childhood presence for my own comfort over the past year. More than one friend has told me they reached for their oldest, most cherished stuffed animal in recent times ā rescuing them from closets or shelves, gently stroking their much-repaired coat and reconnecting with ancient feelings of safety and innocence.

I spent 32 years living without Mister Rice Guy, because I made friends and gained confidence out in the world. But I had forgotten how to play.

Weāve all observed the intense absorption of children at play. As a writer, Iām envious of their ability to invent characters, storylines and games without effort. Imagination is a form of pleasure and escape. Itās not quite like an adult daydream. To play is to live in the present, unremittingly, without distraction or self-judgment. Thereās a sense of discovery and wonder.

Playfulness is a collective trait. āI can walk into any daycare anywhere in this country and see children pretending all day long,ā says Taylor, who wrote the definitive book on pretend friends and has spent her career unraveling the mysteries of why we play. She believes the instinct for imaginary play is universal, and that imagination itself is fundamental to the human condition. And not just for humans. Taylor points to a handful of studies going back to the 1950s that suggest gorillas, chimpanzees and dolphins engage in imaginary play ā among each other or with their human interlocutors.

The āwhyā of it is less evident: Play may serve a profound evolutionary purpose that we still donāt understand. But the capacity for imagination benefits us all our lives ā whether itās to propel us to the moon or to write the occasional poem. We also all have the capacity to think about things that donāt exist, might have been or could be. Thinking about the past, imagining a future: These are the tools of fiction. And what is our daily self-talk if not the adult version of our childhood attempts to cope with these past and future notions?

Who can we be speaking to?

Imaginary friendships werenāt even thought to be good for children until the 1990s, when an efflorescence of research began to suggest otherwise. Today, having fantasies of this nature is considered not just healthy, but an important rite of passage for some. Studies by Taylor and others suggest that up to 65 percent of us had an imaginary friend, or multiple friends, in childhood or adolescence. (Other studies suggest the number is much lower, around 30 percent).

Researchers have found that the presence of an imaginary friend ā whether a wholly-invented figment of a childās imagination or a favorite object like a stuffed animal that has a personality and āconversesā with the child ā tends to correlate with high levels of creativity and empathy. Some of us invented entire worlds with imaginary characters and storylines, called paracosms. In doing so, we gained a whole lot more than companionship.

The benefits also accrue later in life. Several recent studies have shown the experience of having an imaginary companion likely makes adolescents and adults more independent, resilient and prone to ask for help when they need it. And, yes, adults who used to have imaginary friends do engage in more self-talk than other people.

But why might I ā or any of us ā seek a reunion with our pretend playmates? The answer may lie in the disorienting circumstances of our new reality. My childhood world was small and turbulent and vulnerable. Adults were the force majeure, compelling where I went and what I did. Our COVID-19 lives today are similarly proscribed, attenuated and disordered by forces outside our control. Thereās a deadly pandemic on, and not even the grown-ups know whatās going to happen next. Our worlds are again defined by hard boundaries and closed doors. And just like in childhood, we survey our lives in the lonely hours of before-sleep or before-dawn, waiting for the point where we again have something to look forward to.

For me, spending time with Mister Rice Guy helped me realize how big my world truly is, no matter how small it can feel inside the daily closed loop of my pandemic bubble. The last time he and I played together when I was 8, his world was bounded by my green-carpeted bedroom and the fenced-in recess yard behind my school. When he came back to me, we enjoyed a leisurely ramble through the Sonoma County hills all day, hunted for ripe blackberries and compared the personalities of the different cows we ran into (and tried to run up to) on skinny ranchland trails.

After we took those first post-vaccination forays into the world, my fears started to ebb, and Mister Rice Guy stopped coming around. Iām OK with that ā it was a reunion, after all, and this time his departure isnāt the sudden banishment of an ashamed 8-year-old girl. Heās gone away for now. But if living is coping with uncertainty, he could very well be back.

Heāll be welcome. I sleep better these days knowing I have an extra friend who requires no social distancing, who sees me clearly with his every-colored eyes. And whoāll remind me when itās time to play.

© 2025 Julia Scott.