Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Can altering cancer āmindsetsā change physical outcomes?

Wednesday, August 30th, 2023

Longtime oncologist Lidia Schapira had always been struck by the wildly different ways her patients responded, both emotionally and psychologically, to their cancer diagnoses. She noticed something else too: The way people thought about their illness seemed to shape their experience — including their physical response to pain and side effects.

“I’ve had so many people stuck in a catastrophic way of thinking that prevented them from seeking more sources of support,” said Schapira, MD, and director of the Cancer Survivorship Program at Stanford Medicine. “But cancer can also inspire some people to come together and care for each other, to live through and even grow from, these situations.”

Schapira hadn’t had the opportunity to put her observations through scientific rigor until she met psychologist Alia Crum, associate professor of psychology. Crum runs Stanford’s Mind & Body Lab, which focuses on how mindsets affect outcomes both within and beyond the realm of medicine, and has studied how beliefs can alter experience with other physical ailments.

Together with lead author Sean Zion, former Stanford graduate student in the Mind & Body Lab, and other collaborators, Crum created the first targeted digital mindset intervention — an interactive online course — for early-stage cancer. They found early, self-reported evidence that patients who underwent the intervention saw improvements in their quality of life. Results of the study, which, Schapira admitted, exceeded her expectations, were published this month in Psycho-Oncology.

“Not only did it improve outlook, the intervention improved the experience of physical symptoms,” Schapira said of the subjects’ less-bothersome side effects and a decrease in pain levels. “If you are able to actually help your body feel it less or have it bother you less, you are doing yourself an enormous favor. As an oncologist, I can tell you that’s a big deal.”

The mind-body connection

Crum and her team had previously shown how mindset — core assumptions about the nature and meaning of illness — can dictate the body’s response to illness and treatment. For instance, they demonstrated how beliefs can alter patients’ side effects while taking a powerful course of allergy medications. Those who were told at the outset that side effects of the medication were a positive sign that the body was responding to treatment were able to adopt a mindset that ultimately desensitized them to the typical symptoms from treatment, such as rashes, hives, swelling and stomach pain – as opposed to those who were told that symptoms were merely a side effect of the medication.

Cancer was an uncharted area for Crum and she was eager to explore that with Schapira. They worked with colleagues to design a trial that would test out a tantalizing hypothesis – that changing a patient’s mindset about their cancer could produce actual lasting improvements to quality of life amid one of the most stressful and frightening experiences of their lifetimes.

“I’m an interventionist at heart,” Crum said. “We never really know how valuable a mindset is until you try to change it.”

Zion had previously worked with Crum and other researchers in the Mind & Body Lab to characterize common mindsets about cancer. They theorized that adopting a mindset change about cancer from “cancer is a catastrophe” to “cancer is manageable,” or about the body (‘My body is capable ‘ vs ‘my body is an adversary’) could be transformative.

Crum and Schapira designed an interactive online course on cancer mindsets for a large group of newly diagnosed cancer patients undergoing treatment for the first time. They wanted to know whether mindsets matter in the context of cancer outcomes, whether they can be swayed and if such changes would make a measurable difference, behaviorally, socially, emotionally and physically.

The team enrolled 361 participants, all of whom were recently diagnosed with various non-metastatic cancers who were undergoing systemic treatment. For 10 weeks, half the participants watched a series of short videos featuring experts in psychology and oncology as well as cancer survivors, who spoke about how their mindsets changed throughout and after their treatment, and the challenges they faced along the way. Participants then answered prompts. In the final phase of the intervention, they were asked to write a short letter to a recently diagnosed cancer patient, sharing what they had learned from the experience, including the role of their own mindsets. The other half received just the question prompts without the modules or other materials. A follow-up assessment showed these mindset changes persisted after the end of the intervention.

Participants who went through the modules increased their health-related quality of life, such as their emotional well being, physical health and general functioning by 10%, as measured by changes in industry-standard scales. They also found significant improvements in coping skills and patients’ self-reported physical symptom distress decreased too, indicating that overall pain level and side effects were less bothersome. Results from the intervention, which took participants only 2.5 hours to complete, were comparable to those seen after longer, more intensive treatments, such as a 12-week course of cognitive behavioral therapy.

A future cancer treatment?

The study’s authors emphasized that there are no “correct” mindsets when it comes to a cancer diagnosis. The goal was to make participants aware that they have a mindset, and they could choose to shift it should they so choose.

The next study, already in the planning phase, will need to replicate these results with a larger and more diverse sample – the current group skewed 82% female and 85% white. Scientists will also be measuring physiological changes over time, rather than a model solely reliant on self-reporting. In the future they also aim to tailor the treatment to other conditions, including patients with metastatic cancers.

The team hopes that, with continued positive results from subsequent studies, a version of this treatment could one day be prescribed directly by physicians to cancer patients as an upstream intervention tool that can be deployed before symptoms of emotional trauma have taken root. It could serve as an adjunct to other forms of cognitive therapy.

“If we can make the treatment phase less traumatic with fewer symptoms needing to take fewer adjunct medications, I think the path out of cancer treatment into survivorship will be easier as well,” said Schapira.

Tags: Cancer, Placebo Effect, Stanford Medicine

Posted in Front Page, Uncategorized | Comments Off on Can altering cancer āmindsetsā change physical outcomes?

The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Thursday, January 20th, 2022

Hereās the last time I remember playing with my childhood imaginary friend, Mister Rice Guy. Iām 8, and itās my least favorite time of day: recess. Iām friendless and alone at my new school, and so I bring him with me that day ā normally he stays home. We walk the perimeter of the chain-link enclosed yard behind the school as kids around us scream and play. My classmates assume Iām talking to myself, so they start mouthing my words, wreathing them with derisive laughter.

Until that day, my imaginary friend had been a source of comfort. That moment transformed him into a source of shame. Mister Rice Guy (whose name I am sure I took from misunderstanding the phrase āMister Nice Guyā) disappeared.

Thirty-two years later, in the nadir of a global pandemic, he came back again. But more on that in a moment.

According to my parents, Mister Rice Guy first showed up when I was 5. I was an awkward only child with a need for an imaginary companion who understood me. I was very private about him. He never came to the dinner table, and I never told my parents what he looked like. He and I spent long hours locked in conversation, playing together on the floor of my green-carpeted bedroom. What did he look like? In later years, Iāve been embarrassed to admit I couldnāt quite remember. What I do know is how he made me feel. Safe and warm. Seen, heard and protected.

Maybe you had a special friend in childhood who made you feel that way. Or more than one. The experience exists on a spectrum, stretching from conversations with a favorite toy or stuffed animal to personified imaginary entities like mine.

For the most part, children know these friends are āpretend.ā Thatās the point. Theyāre not a delusion, but rather a way to access feelings and qualities that our youthful selves know to be important, but which weāre not ready to claim as part of our essential identities. Theyāre our emotional backpacks, apart but close at hand, there when needed to deliver a store of strength or calm.

Experts say a childās imaginary friend can be someone to consult when making a decision. They can make us feel better about our peer relationships, giving us insights on how to handle friendships and disagreements. And they offer the capacity to imagine new outcomes to difficult situations. Feeling trapped and confused, say, in a pandemic? Your imaginary friend might help you imagine a way out.

āThe kind of mind that can reason about the past and think about the future is the kind of mind that can come up with an alternative,ā says Marjorie Taylor, a professor emerita of psychology at the University of Oregon. Taylor has studied childrenās fantasy lives for decades. I called her up recently to ask if I was crazy, because suddenly Mister Rice Guy was back.

No, she said. I was not crazy. In fact, more adults could benefit from finding new ways to play.

In the shortest, darkest days of that first fearful winter, as COVID-19 mutations circled the globe, I sat at home, hushed and frightened and uncertain. From bleary days to long, insomniac nights, a heaviness assailed me in my solar plexus. It dragged me down and made me cry, on and off, for days at a time. And then suddenly, one night, all I could think of was Mister Rice Guy. I swore I could feel his presence in my bedroom.

Was I losing my mind? I looked around in the dark and felt like a fool. Why would my old companion be back in my life? Could he even recognize this sad, 40-year-old variation on the (also kind of sad) child he had comforted at the age of 8?

The next morning, I woke up, exhausted and confused, and took a hike for the first time in months. I drove to a hilly park with fresh green grass. At the outset, I wondered if Mister Rice Guy would tag along, but still it made no sense. Why would my old companion want a friend like me? I was weepy and depressed and old. If he were there, heād want to play.

Suddenly I knew what I needed to do. I took off my pack, climbed a medium-size hill, waited until no one else was looking ā and rolled down that hill. I collapsed at the bottom, giggly and dizzy and covered in burs. You cannot be sad after you roll down a hill. And I know for a fact that I didnāt roll down that hill all by myself. I got a push from Mister Rice Guy.

After that, we spent a lot of time together. As the first pandemic winter yielded to its second spring, I left my apartment as often as I could, taking long walks where I paid special attention to bird and insect worlds. What were their days like? I imagined walking side by side with Mister Rice Guy on these explorations, which made them feel adventurous and fun. That line of ants streaming by a smeared banana ā where was their nest? (We tried to follow the trail of ants for as far as we could.) How closely could we sneak up next to the hummingbirds on my street before they zoomed away? By then Iād realized, to my delight, that I hadnāt forgotten what my childhood friend looked like: He looked like no one, or like everyone who isnāt me. In an era that seems all too ready to demonize the Other, here was a presence of pure Otherness, radiating the acceptance I hadnāt been able to access on my own.

If someone saw me talking to myself, let them wonder. I felt no shame.

Iām sure I am not alone in having invoked a childhood presence for my own comfort over the past year. More than one friend has told me they reached for their oldest, most cherished stuffed animal in recent times ā rescuing them from closets or shelves, gently stroking their much-repaired coat and reconnecting with ancient feelings of safety and innocence.

I spent 32 years living without Mister Rice Guy, because I made friends and gained confidence out in the world. But I had forgotten how to play.

Weāve all observed the intense absorption of children at play. As a writer, Iām envious of their ability to invent characters, storylines and games without effort. Imagination is a form of pleasure and escape. Itās not quite like an adult daydream. To play is to live in the present, unremittingly, without distraction or self-judgment. Thereās a sense of discovery and wonder.

Playfulness is a collective trait. āI can walk into any daycare anywhere in this country and see children pretending all day long,ā says Taylor, who wrote the definitive book on pretend friends and has spent her career unraveling the mysteries of why we play. She believes the instinct for imaginary play is universal, and that imagination itself is fundamental to the human condition. And not just for humans. Taylor points to a handful of studies going back to the 1950s that suggest gorillas, chimpanzees and dolphins engage in imaginary play ā among each other or with their human interlocutors.

The āwhyā of it is less evident: Play may serve a profound evolutionary purpose that we still donāt understand. But the capacity for imagination benefits us all our lives ā whether itās to propel us to the moon or to write the occasional poem. We also all have the capacity to think about things that donāt exist, might have been or could be. Thinking about the past, imagining a future: These are the tools of fiction. And what is our daily self-talk if not the adult version of our childhood attempts to cope with these past and future notions?

Who can we be speaking to?

Imaginary friendships werenāt even thought to be good for children until the 1990s, when an efflorescence of research began to suggest otherwise. Today, having fantasies of this nature is considered not just healthy, but an important rite of passage for some. Studies by Taylor and others suggest that up to 65 percent of us had an imaginary friend, or multiple friends, in childhood or adolescence. (Other studies suggest the number is much lower, around 30 percent).

Researchers have found that the presence of an imaginary friend ā whether a wholly-invented figment of a childās imagination or a favorite object like a stuffed animal that has a personality and āconversesā with the child ā tends to correlate with high levels of creativity and empathy. Some of us invented entire worlds with imaginary characters and storylines, called paracosms. In doing so, we gained a whole lot more than companionship.

The benefits also accrue later in life. Several recent studies have shown the experience of having an imaginary companion likely makes adolescents and adults more independent, resilient and prone to ask for help when they need it. And, yes, adults who used to have imaginary friends do engage in more self-talk than other people.

But why might I ā or any of us ā seek a reunion with our pretend playmates? The answer may lie in the disorienting circumstances of our new reality. My childhood world was small and turbulent and vulnerable. Adults were the force majeure, compelling where I went and what I did. Our COVID-19 lives today are similarly proscribed, attenuated and disordered by forces outside our control. Thereās a deadly pandemic on, and not even the grown-ups know whatās going to happen next. Our worlds are again defined by hard boundaries and closed doors. And just like in childhood, we survey our lives in the lonely hours of before-sleep or before-dawn, waiting for the point where we again have something to look forward to.

For me, spending time with Mister Rice Guy helped me realize how big my world truly is, no matter how small it can feel inside the daily closed loop of my pandemic bubble. The last time he and I played together when I was 8, his world was bounded by my green-carpeted bedroom and the fenced-in recess yard behind my school. When he came back to me, we enjoyed a leisurely ramble through the Sonoma County hills all day, hunted for ripe blackberries and compared the personalities of the different cows we ran into (and tried to run up to) on skinny ranchland trails.

After we took those first post-vaccination forays into the world, my fears started to ebb, and Mister Rice Guy stopped coming around. Iām OK with that ā it was a reunion, after all, and this time his departure isnāt the sudden banishment of an ashamed 8-year-old girl. Heās gone away for now. But if living is coping with uncertainty, he could very well be back.

Heāll be welcome. I sleep better these days knowing I have an extra friend who requires no social distancing, who sees me clearly with his every-colored eyes. And whoāll remind me when itās time to play.

Tags: childhood, COVID-19, Dr. Marjorie Taylor, Imaginary friends, Julia Scott, pandemic, Paracosms, The power of play

Posted in Front Page, Uncategorized | Comments Off on The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Duolingo: Extreme Sports Heroes

Thursday, March 11th, 2021

EPISODE PART 1:

Sibusiso and the Big Mountain

Sibusiso Vilane has stood at the summit of the worldās tallest mountains. He is a mountaineering icon from South Africa, who has ascended Mt. Everest twice. He has reached the greatest heights in the world… but growing up, he never even thought about climbing a single mountain, until fate intervened and changed the direction of his life forever.

His first conquest of Everest put him in the history books as the first Black man from Africa to make it to the top. But the message he carried back to all South Africans was even more important to Sibusiso: one of equality of potential and ability, at a time when the country was still emerging from the painful legacy of apartheid.

EPISODE PART 2:

Bianca’s Big Wave

Bianca is a professional extreme surfer. She has surfed big waves all over the world. But there was always one wave that scared her the most: the Mavericks surf break, in California. Along the way, conquering Mavericks also became a battleground to fight for equal opportunities for women in surfing.

Today, thanks to the advocacy of Bianca and other female surfers, surf contests are starting to treat women equally to men — including them in all the major contests and awarding them the same prize money when they win. But the fight is far from over.

Tags: Bianca Valenti, big-wave surfing, Duolingo, extreme sports, Julia Scott, Mavericks, Mavericks surf contest, mountaineering, Mt. Everest, podcast, Sibusiso Vilane, South Africa

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

The Daring Cities Podcast

Wednesday, October 7th, 2020

When it comes to solving the climate crisis, cities have an unprecedented opportunity. We already have the tools to cut greenhouse gas emissions from cities by close to 90 percent in the next 30 years. We just need to empower leaders and residents to adopt them. Cities will help chart the future course of life on Earth, and thousands of them are stepping up to fight climate change. Some are flat-out daring, finding ways to navigate major opposition as they go.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and a worldwide recession, the stakes for a green recovery couldn’t be higher. Join host Julia Scott as she visits with city leaders in seven daring cities, in countries as diverse as the Philippines, Japan, Argentina, and the USA.

STREAM EPISODES HERE

SUBSCRIBE via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and Luminary.

The Daring Cities podcast was sponsored by the ICLEI ā Local Governments for Sustainability.

Tags: Bill Peduto, Buenos Aires, COVID-19 recovery, Daring Cities, Green building, ICLEI, Julia Scott, Malmƶ, Nagano, Orlando, Pasig City, Pittsburgh, podcast, Sustainable Cities, Turku, UN, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Urban planning podcast

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

Duolingo: Two Unexpected Entrepreneurs

Thursday, August 20th, 2020

EPISODE PART 1:

She Can Fix It

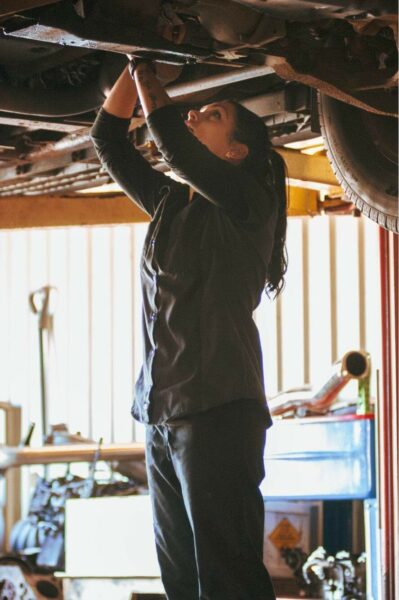

Stephanie Lopez is a woman in a manās profession, something some men have never let her forget.

Stephanie, a mother of two, owns Woosters Garage in Weston, a small town in central Wisconsin. She named her garage after her great-great grandfather Glen Wooster, the first in a long family line of men ā including her grandfather and father ā who love fixing carsā¦ a passion she inherited.

Today, Stephanie Lopez is proud to run her own garage. But her road there was bumpy, winding and full of unexpected barriers.

EPISODE PART 2:

Silicon Valleyās Wizard of Jobs

Rahim Fazal seemed destined for a thriving career in the tech industry when the web company he co-founded as a teenager made him a millionaire overnight.

Rahim is 38 today. His dreams of making it in Silicon Valley eventually did come trueā¦ But along the way, he noticed that not everybody was equally welcome there. The troubling question of who gets to belong in the heart of the tech world ā and who doesnāt ā eventually led Rahim to take the biggest leap of his career.

Tags: Duolingo, Entrepreneurs, inspiring, Joel Scott, Julia Scott, podcast, Rahim Fazal, Silicon Valley, Stephanie Lopez, SV Academy, Woosters Garage

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | Comments Off on Duolingo: Two Unexpected Entrepreneurs

Under One Roof: How COVID-19 Turned My Apartment Building Into a Community

Thursday, April 16th, 2020

I live in a tall condo building with hundreds of neighbours in Oakland, California. The San Francisco Bay Area has been under lockdown for five weeks now, though many of us have already lost count.

These are long days. Sometimes I forget to eat. I sit in front of my laptop at my kitchen table ā which is also my dining room table ā and mark time by counting the number of delivery vans in the driveway from Amazon. Everyone in my building is ordering in and no one is venturing out.

And I’ve started to wonder: how are we all coping? How has the coronavirus changed our lives so far, and how will it change us as a building? As neighbours?

We live solitary lives behind our 119 doors. And yet we’ve never had more in common. The threat we face from outside is invisible, terrifying and real. And all of a sudden, we’ve come to depend on each other to stay healthy. One person’s COVID-19 exposure could endanger others in proximity. We all need to protect each other at the same time.

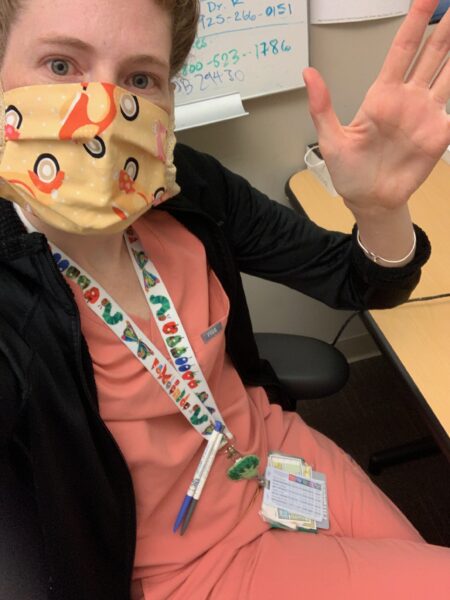

Possibly no one in the building understands the threat better than Katie Stephenson. She’s a pediatrics resident at a local hospital, and she lives on the second floor. She regularly works 12-hour shifts at the hospital, where she sees children who have been admitted because their parents are afraid they might have COVID-19.

‘I just assume that I’ve been exposed’

When she comes home from work, the first thing she does is strip off her scrubs and take a long shower with a lot of soap. “Because it’s not only just the germs, but it’s also the sweat and everything from being in the hospital and trying to sleep on the little cots there, and being exposed to all the coughing,” she says.

Katie is not just trying to stay clean. She’s trying to protect our neighbours from the coronavirus ā since she thinks it’s only a matter of time before she becomes infected herself.

I just assume that I’ve been exposed, or that I’ll be exposed again. So my mission is just to keep my germs confined to my little space and not let them get out,” she shrugs.

Kate Stephenson at work at Oakland Medical Center.

The prospect of infection doesn’t scare her. But she knows she could infect our neighbour Judy Rosenberg, a woman in her 70s who lives just two doors down. Judy is an improvisational pianist who keeps a concert piano in her living room. She doesn’t find herself wanting to play that much these days, though.

“I just feel an overriding sadness, and I have felt depression in my life. The amount of deaths per day is just staggering to me,” she says. “I’m in my early 70s and nothing like this has ever happened to my generation. Even 9/11 was horrible ā¦ but it was an event; it came and it went.

“This is of a different character, and this has a quality of war to it,” she adds.

Judy’s days revolve around not getting sick; the outcome would likely be far worse for her than for Katie. She still goes out every day with a mask on for walks and groceries, but she’s shut in the rest of the day, emailing friends and reading spy novels to pass the time. She tries not to watch the news.

Katie and Judy’s lives have little in common, but it struck me that ā now more than ever ā what we do to protect each other makes a stark difference ā maybe even between life and death.

Our land-based cruise ship

Gina Belleci and her girlfriend Jessica Holt, my neighbours on the sixth floor, made their unit into a shared office space after the lockdown. They settled into a routine, dropping food off for Gina’s mom once a week to keep her from being exposed in the grocery aisles. They also took care of their neighbours, shopping for an elderly friend on the eighth floor who really should not leave the building.

But as the news worsened and the disease’s virulence became more widely understood, they made the difficult decision to clear out of our building and go live with Gina’s mom. They were worried that living with 180 people gave them more potential exposure to COVID-19, and they feared transmitting it to Gina’s mom on those weekly visits.

“I either need to choose being with my mom, or we need to really commit to this land-based cruise ship we live on, which is so big and has so many people coming in and out. And quite frankly, I don’t know that anything’s being cleaned above and beyond,” says Gina.

“Land-based cruise ship.” I hadn’t quite thought of it that way, but there is a concern here about sanitation. Our building’s maintenance man has gone home, and there is no cleaning going on. All of the building’s common touch points could now be vectors for infection. Elevator buttons. Door knobs. I’ve taken to wearing gloves just to go downstairs. When people see me inside an elevator they’re waiting for, they give a tight smile and wait for the next one. Even the mailroom has started to feel a little snug.

But a lot of nice little things have happened in my building, too. Several neighbours left notes on the bulletin board in the lobby, offering to help anyone who needs it. On

e person organized the entire seventh floor into a group text, so that when someone’s leaving for a grocery run, they can take requests and minimize the number of trips from the building.

We’re also connecting in new ways. My sixth-floor neighbour Guillaume Chartier, a fellow Montrealer, dropped off a slice of homemade lemon meringue pie after I interviewed him for this story. I had my first real conversation with my third-floor neighbour Ernesto Victoria, who has lived above me for five years but with whom I’ve mostly exchanged only pleasantries.

And after a few people started meeting on the roof to watch the sunset, it turned into a socially-distant Friday happy hour where everyone brings their own drink and stands at least two metres apart.

This pandemic has changed our world, but it has also changed our building. I’ve met more neighbours in the last week than I’ve gotten to know in the past five years. I already feel better knowing I have so many people to talk to who are facing the same situation ā the same questions ā as I am. We may all be behind our doors for now, but we really are in this together.

Tags: CBC, Coronavirus, COVID-19, Julia Scott, The Current

Posted in Front Page, Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

Beyond #MeToo: Do Hormones Make the Man?

Friday, January 26th, 2018

Expressing Masculinity: It’s Complicated

Deep down, men and women have more in common than they differ — like 22 out of 23 pairs of chromosomes. ButĀ there’s one thing men have more of: testosterone. Conservative commentator Andrew Sullivan recently argued that higher levels of testosterone underscore natural sexual differences.

But when issues of gender identity, sexuality and personal choices are added to the mix, the question of expressing masculinities becomes even more complicated.

Julia Scott talked to two people who are exploring their manhood today with a little help from testosterone.

One is Eric Trefelner, a physician living on Montara, Calif. who recently experimented with injecting testosterone to bulk up for his workouts. But along the way, he started experiencing sensations he never expected to feel.

“I had more energy. I felt more powerful. I felt more sexual. I felt more ability to take risks,” Trefelner said.

Heād always identified as a man, but he suddenly felt a sense of communion with men at the gym — a form of acceptance heād missed out on as a kid.

“I used to always have these dreams where I was near men, they were in a group distant from me. I would feel so sad and wake up crying because I was separated from the world of men. … And all of a sudden I was feeling like, this is what it means to be a man!”

Was Trefelner discovering something that had lived inside him all along? Or was it a new reality? If was just the hormones, would he lose access to the special feeling if he stopped injecting?

Medical science had a specific answer to this question when testosterone was synthesized in 1935 and marketed as a male-enhancing sex hormone for straight men.

Meanwhile, gay men were made to take it to reverse their so-called “endocrine disturbance,” a completely made-up idea that if they took a “manly” hormone they would be less turned on by men (Though doctors noticed pretty quickly that it actually tended to enhance their attraction to other men).

So not only can you be a man without feeling like one, you can feel like a man without beginning life as one.

Addison Beaux, a writer who lives in Palo Alto, said that even as a 5-year-old, he identified as a boy and asked everyone to call him Bob.

Addison Beaux, a writer living in Palo Alto, California. (Addison Beaux)

But it wasn’t until he turned 40 that Beaux decided to make a physical, surgical transition to a male appearance. But taking testosterone was a less obvious decision, and Beaux gave it a lot of thought before deciding to do it. That’s because, unlike Trefelner, he wasnāt shocked to feel like a man. He never perceived himself as anything but.

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve always been masculine more from the inside, so I’ve always felt that way and I still feel that way. Hormones do not necessarily make the man.”

The hormones were just the finishing touch. Beauxās gender transition has taken a lifetime — and itās still in process.

This story was part of a series on KQEDās TheĀ CaliforniaĀ Report, Beyond #MeToo: Sex, Abuse and Power Through a California Lens .

Tags: #MeToo, KQED, The California Report

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

Beyond #MeToo: Teaching Boys About Consent

Wednesday, January 24th, 2018

Coaching Boys Into Men

When is the right time to start teaching young boys about consent, boundaries and respect toward women?

A nationwide program called Coaching Boys Into Men trains school coaches to work with boys as young as 11, who are on their school’s athletic teams. Boys trust their coaches, and the conversations that ensue are designed to plant seeds that will help prevent abuse — and give young men the tools to speak up when they see something that’s not right.

Student athletes are often the leaders at their schools, and they can set the tone for the other students.

At Petaluma Junior High School, former student Danny Marzo and Athletic Director Zach Dee told us about how the program has led to changes on a personal level in the school culture overall.

This story was part of a series on KQED’s TheĀ CaliforniaĀ Report, Beyond #MeToo: Sex, Abuse and Power Through a California Lens .

Tags: #MeToo, Julia Scott, KQED, The California Report

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

Heavyweight episode: “Julia”

Tuesday, November 8th, 2016

What happens when you go back and open the door to a time in your childhood that you tried to forget? Heavyweight host Jonathan Goldstein and I found out together.

Tags: bullies, bullying, Gimlet Media, Heavyweight, Jonathan Goldstein, Julia Scott, Montreal, podcast

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work, Uncategorized | No Comments »

© 2025 Julia Scott.