Posts Tagged ‘COVID-19’

Shut In Together: 119 Neighbors and Me in an Oakland Condo

Wednesday, April 30th, 2025

I have a confession. I don’t know most of my neighbors. I don’t even know the names of everyone on my floor. I live in a tall condo building in Oakland, with a towering view of Piedmont and the surrounding neighborhoods. It’s the kind of building where you can nod to a neighbor for years, without thinking about the interaction.

No more. Because right now, almost all of us are home together. Thinking about, or trying not to think about, the virus. Our lives intersect in new ways. Our interactions will follow suit.

COVID-19 has transformed my world. My one-bedroom is now my office, tiny gym and portal to the friends I miss hugging and to my parents, who are holed up in the North Bay and haven’t set foot outside since shelter-in-place orders took effect.

In recent days, I‚Äôve struggled with my emotions and video chatted with my therapist. I‚Äôve had good days when I am overwhelmed with gladness to be part of a team at KQED whose coverage of this pandemic, deemed an ‚Äúessential service,‚ÄĚ has become more essential than ever.

I’m not the only one in my building who’s struggling to find our way in a new landscape with no view of the horizon. The coronavirus is an unspoken part of every interaction. And the fear is there, too. We fear getting each other sick, and we fear what might happen to us if we were to fall ill. My 119-unit building has about 180 residents. For the next few weeks or months, we’ll almost all be living and working here in our little units, separated by a concrete wall and under one roof. I started wondering: How are we all coping so far?

Our ‚ÄėLand-Based Cruise Ship‚Äô

I put up a note on the bulletin board in the mail room, asking my neighbors to reach out and tell me their stories. The first one who did was Gina Belleci, who lives on the sixth floor. She and her girlfriend, Jessica Holt, have been sheltering together since Gina’s startup sent everyone home. She now telecommutes from a small table wedged next to the kitchen, while Jessica works with her laptop propped up on a dresser in the bedroom.

Gina says some of her days are spent in ‚Äúsilent panic‚ÄĚ mode. Other times, she feels optimistic. Gina and Jessica take care of their neighbors. Lately they’ve been handing out toilet paper and grocery shopping for an elderly friend on the eighth floor, who really should not leave the building.

‚ÄúI think we just really need to band together. And these small, tiny ways really add up,‚ÄĚ said Gina. ‚ÄĚIt’s generosity breeds generosity. I feel really excited to be part of this building to see what happens here.‚ÄĚ

Jessica is a freelance theater director, and she told me that her prospects have become extremely uncertain, very quickly. All of her upcoming theater productions have been canceled, and the same is true industry-wide.

‚ÄúThis is all I’ve really practiced as a trade, as a craft, my entire life,‚ÄĚ she told me. ‚ÄúI’m not going to lie ‚ÄĒ the other night, I sort of threw myself into a little heap. And I and I keep saying, well, we’re going to get through this. There will come a time when we return to normal. But will we? Will we ever be able to return to normal? I don’t know.‚ÄĚ

They told me that they’ve made the difficult decision to leave. Gina’s 74-year-old mother lives in Antioch and doesn’t have anyone to take care of her. They worry that the longer they spend in a building with 180-odd people, the likelier they are to pick up the coronavirus and bring it back to Gina’s mother.

‚ÄúI either need to choose being with her, to be able to go get things for her just to keep her in the house, or we need to really commit to this land-based cruise ship we live on ‚ÄĒ which is so big and has so many people coming in and out,‚ÄĚ said Gina.

So they’ve packed their suitcases for a month and said goodbye to their neighbors.

She’s right about the sanitation issue. Our building’s maintenance man has gone home, and there is no cleaning regime, which I suspect is true of many large apartment buildings here in the Bay Area.

In a building like mine, where space is limited, it’s nice to be able to open your door and have a conversation with someone you meet by the elevators or in the mailroom. But each of those touch points now could be vectors for infection. Elevator buttons. Door knobs. I’ve taken to wearing gloves just to go downstairs or when I’m in the laundry room. When people see you inside an elevator they’re waiting for, they give a tight smile and wait for the next one. Even the mailroom has started to feel a little snug. People don’t linger to enjoy those conversations anymore.

So it was a pleasure to receive a text from my neighbor Dina Mackin on the third floor. ‚ÄúWant to meet up on the roof to see the sunset?‚ÄĚ it read.

Dina Mackin.

When I got there, Dina had a glass of ros√© in her hand and was standing in front of a darkening view of West Oakland and in the distance, the Golden Gate Bridge. ‚ÄúThis is what I have to do every day to keep my sanity,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúThe beauty of just seeing something so simple that happens every single day, that marks the passing of time. You just appreciate it more and more. And this is the time to appreciate it.‚ÄĚ

As she spoke, I realized that I hadn’t been outside in two days. This was the first time I’d tasted fresh air. When days start to run together, watching the sunset is an important form of closure. Even better to watch it with a neighbor.

Dina agreed. ‚ÄúThis is one of the few things we’re still able to do,‚ÄĚ she said.

On the Front Lines

Katie Stephenson, my neighbor on the second floor, cannot shelter in place because she is a second-year pediatrics resident at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center. I barely see her as she darts in and out to shower, sleep and drink some coffee before heading back out to the hospital for another 12-hour shift.

I spoke to her on an evening she had just tested negative for COVID-19. She had a post-allergy season cough so her doctor sent her to have a test. But she assumes that it’s only a matter of time before she does get the coronavirus, so she’s careful to limit her contacts within the building.

‚ÄúMy mission is just to keep my germs confined to my little space and not let them get out,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúBut I also think that if I’m one of the people who gets COVID-19, that I would do fine ‚ÄĒ most people my age, if we‚Äôre healthy, we do fine. I think a lot of people in my residency program, myself included, are very likely to get it and are very likely to do fine.‚ÄĚ

Katie has been on the pediatrics ward for the past three weeks. She sees children who have been admitted because their parents are afraid they might have COVID-19. All medical staff must wear personal protective equipment ‚ÄĒ essentially hazmat suits ‚ÄĒ and masks around the children, which is profoundly unsettling.

‚ÄúThere are nurses wearing the suits, and there’s multiple doctors coming in wearing the suits. It‚Äôs scary,‚ÄĚ she said. She tries to defuse the fear by making her young patients smile. ‚ÄúI have some stickers that my mom sent for St. Patrick’s Day. They’re all green. And so I have been bringing in stickers and putting them on my suit. Or I‚Äôll draw like a smiley face, to be a big yellow smiley-face person.‚ÄĚ

Katie‚Äôs supervisor has told her group that they‚Äôre running a marathon, and so far they‚Äôve only run half a mile. They need to remember to pace themselves. Luckily, Katie is an actual marathon runner ‚ÄĒ she‚Äôs done three of them ‚ÄĒ so she knows when to push herself. Her freezer is stuffed with homemade dinners prepared by her mother ‚ÄĒ a source of comfort at the end of another long day.

My neighbor Alexa Eurich is also running a marathon of sorts. Somehow, she’s had to find a way to teach her combined classroom of kindergarten and first grade students from her apartment on the fourth floor. Eurich has taught at Aurora School in Oakland for 15 years. The school closed down so quickly that no one had time to grab enough teaching supplies for a month, let alone the rest of the school year.

‚ÄúWhen you hear about teaching kindergarten remotely, you just have to laugh … because how is that even humanly possible?‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúIt’s been very hard not knowing, because I’ve felt competent at my job for a very long time.‚ÄĚ

Alexa has 16 kids in her classroom. She manages to video chat with four of them each day, in addition to checking in regularly with teachers and parents. She’s trying to keep up with the lessons her kids were learning two weeks ago, but she has to improvise with whatever books the students have around the house. They have to be trained to talk to her through a computer screen. It can be hard to connect.

‚ÄúI know without a doubt that the best way we humans learn is through a relationship. And not being with them physically when they’re at this developmental stage is very trying to the relationship,‚ÄĚ she said.

It’s also been trying for her. Because she is in remote meetings all day, her husband has to stay in the bedroom for hours at a time.

‚ÄúI’ve been working from, like, six o’clock in the morning to about six o’clock at night,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúAnd I am still in love with teaching. I love my job. But I’m not in love with this job right now. I have to learn how to do it in a way that feels wrong to me.‚ÄĚ

Staying Sane Inside Four Walls

I asked my neighbors what they are doing to stay sane amid deeply uncertain circumstances. My neighbor Guillaume Chartier and his husband Grant Eshoo have been baking lemon meringue pie and watching ‚ÄúStar Trek: The Next Generation‚ÄĚ after they have finished the day‚Äôs work at their improvised desks in the living room. (Guillaume is an animator, and Grant works for Alameda County).

They chose to re-watch Star Trek for its nostalgia, but are finding that it holds surprising relevance to our present moment on Earth.

‚ÄúThere was an episode where they were facing a lethal epidemic and they had to take measures to contain it,‚ÄĚ said Guillaume. Of course, they succeeded ‚ÄĒ thanks to Dr. Beverly Crusher.

‚ÄúIt displays a very earnest, optimistic outlook on humankind. And we’re just the kind of nerds that we enjoy watching it together,‚ÄĚ he added with a laugh. ‚ÄúIt’s all imaginary settings, but it touches on very current real human conditions and phenomena.‚ÄĚ

My second-floor neighbor Judith Rosenberg is in her mid-70s. She reckons she now spends 90% of her time indoors, except for a brisk daily walk or to pick up groceries. She escapes into serial mysteries and spy novels by authors like John le Carr√© and Charles Cumming. She also emails with her friends, which alleviates some of the ‚Äúoverriding sadness‚ÄĚ she has started to feel.

‚ÄúI have felt depression in my life. I‚Äôve felt all sorts of emotions, but I don’t get sad very much. This is a deep sadness,‚ÄĚ she said.

Her other great comfort is music. Judy has a gleaming concert piano in her apartment. Her specialty is musical improvisation.

‚ÄúI feel a certain life force when I‚Äôm playing,‚ÄĚ she told me. ‚ÄúWhen I sit down to play, there’s something about that experience that makes me feel more alive in a way. And it is a great gift.‚ÄĚ

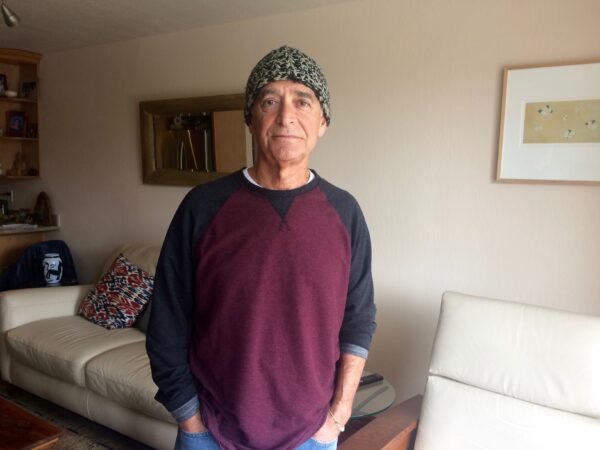

Ernesto Victoria at home. (Julia Scott)

My third-floor neighbor Ernesto Victoria is also in his 70s. He isn’t much of a worrier, but he did get concerned a few weeks ago when he developed a cough. His doctor assessed his symptoms and ruled out the coronavirus. Still, the cough has been hard to shake.

‚ÄúI get a little scared from time to time, I have to be honest with you,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúThe other day, the symptoms were really bothering me. And I just got really emotional.‚ÄĚ

He pulled out his computer and started writing memories of his childhood in Mexico and of growing up with his seven siblings.

‚ÄúMaybe there was this thought, you know, of, ‘If I die, I want my daughters to see this,‚Äô ‚ÄĚ he laughed. ‚ÄúI was just feeling sentimental and emotional.‚ÄĚ

Ernesto loves swimming, biking and hiking. With his pool closed and his favorite biking and hiking trails off limits, his daily pleasures include video chats with faraway friends.

‚ÄúIt is so good to see a face and to talk. It’s the joy of talking with somebody after being sequestered for so long,‚ÄĚ he said.

A lot of nice little things have happened in my building over the past two weeks. I was happy when Ernesto accepted my offer to shop for him sometime soon. Someone on the third floor left a message on the bulletin board offering to help anyone who needs it. Another neighbor organized the entire seventh floor into a group text, so that when someone’s leaving for a grocery run, they can take requests and minimize the number of trips from the building.

I know this virus will escalate in the next few weeks. The news will get scarier. But I’ve met more neighbors in the last week than I’ve gotten to know in the past five years. I already feel better knowing I have so many people to talk to who are facing the same situation, the same questions, as I am. We may all be behind our doors for now, but we really are in this together.

Tags: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Julia Scott, KQED, shelter-in-place, The California Report

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work | No Comments »

The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Thursday, January 20th, 2022

Here‚Äôs the last time I remember playing with my childhood imaginary friend, Mister Rice Guy. I‚Äôm 8, and it‚Äôs my least favorite time of day: recess. I‚Äôm friendless and alone at my new school, and so I bring him with me that day ‚ÄĒ normally he stays home. We walk the perimeter of the chain-link enclosed yard behind the school as kids around us scream and play. My classmates assume I‚Äôm talking to myself, so they start mouthing my words, wreathing them with derisive laughter.

Until that day, my imaginary friend had been a source of comfort. That moment transformed him into a source of shame. Mister Rice Guy (whose name I am sure I took from misunderstanding the phrase ‚ÄúMister Nice Guy‚ÄĚ) disappeared.

Thirty-two years later, in the nadir of a global pandemic, he came back again. But more on that in a moment.

According to my parents, Mister Rice Guy first showed up when I was 5. I was an awkward only child with a need for an imaginary companion who understood me. I was very private about him. He never came to the dinner table, and I never told my parents what he looked like. He and I spent long hours locked in conversation, playing together on the floor of my green-carpeted bedroom. What did he look like? In later years, I’ve been embarrassed to admit I couldn’t quite remember. What I do know is how he made me feel. Safe and warm. Seen, heard and protected.

Maybe you had a special friend in childhood who made you feel that way. Or more than one. The experience exists on a spectrum, stretching from conversations with a favorite toy or stuffed animal to personified imaginary entities like mine.

For the most part, children know these friends are ‚Äúpretend.‚ÄĚ That‚Äôs the point. They‚Äôre not a delusion, but rather a way to access feelings and qualities that our youthful selves know to be important, but which we‚Äôre not ready to claim as part of our essential identities. They‚Äôre our emotional backpacks, apart but close at hand, there when needed to deliver a store of strength or calm.

Experts say a child’s imaginary friend can be someone to consult when making a decision. They can make us feel better about our peer relationships, giving us insights on how to handle friendships and disagreements. And they offer the capacity to imagine new outcomes to difficult situations. Feeling trapped and confused, say, in a pandemic? Your imaginary friend might help you imagine a way out.

‚ÄúThe kind of mind that can reason about the past and think about the future is the kind of mind that can come up with an alternative,‚ÄĚ says Marjorie Taylor, a professor emerita of psychology at the University of Oregon. Taylor has studied children‚Äôs fantasy lives for decades. I called her up recently to ask if I was crazy, because suddenly Mister Rice Guy was back.

No, she said. I was not crazy. In fact, more adults could benefit from finding new ways to play.

In the shortest, darkest days of that first fearful winter, as COVID-19 mutations circled the globe, I sat at home, hushed and frightened and uncertain. From bleary days to long, insomniac nights, a heaviness assailed me in my solar plexus. It dragged me down and made me cry, on and off, for days at a time. And then suddenly, one night, all I could think of was Mister Rice Guy. I swore I could feel his presence in my bedroom.

Was I losing my mind? I looked around in the dark and felt like a fool. Why would my old companion be back in my life? Could he even recognize this sad, 40-year-old variation on the (also kind of sad) child he had comforted at the age of 8?

The next morning, I woke up, exhausted and confused, and took a hike for the first time in months. I drove to a hilly park with fresh green grass. At the outset, I wondered if Mister Rice Guy would tag along, but still it made no sense. Why would my old companion want a friend like me? I was weepy and depressed and old. If he were there, he’d want to play.

Suddenly I knew what I needed to do. I took off my pack, climbed a medium-size hill, waited until no one else was looking ‚ÄĒ and rolled down that hill. I collapsed at the bottom, giggly and dizzy and covered in burs. You cannot be sad after you roll down a hill. And I know for a fact that I didn‚Äôt roll down that hill all by myself. I got a push from Mister Rice Guy.

After that, we spent a lot of time together. As the first pandemic winter yielded to its second spring, I left my apartment as often as I could, taking long walks where I paid special attention to bird and insect worlds. What were their days like? I imagined walking side by side with Mister Rice Guy on these explorations, which made them feel adventurous and fun. That line of ants streaming by a smeared banana ‚ÄĒ where was their nest? (We tried to follow the trail of ants for as far as we could.) How closely could we sneak up next to the hummingbirds on my street before they zoomed away? By then I‚Äôd realized, to my delight, that I hadn‚Äôt forgotten what my childhood friend looked like: He looked like no one, or like everyone who isn‚Äôt me. In an era that seems all too ready to demonize the Other, here was a presence of pure Otherness, radiating the acceptance I hadn‚Äôt been able to access on my own.

If someone saw me talking to myself, let them wonder. I felt no shame.

I‚Äôm sure I am not alone in having invoked a childhood presence for my own comfort over the past year. More than one friend has told me they reached for their oldest, most cherished stuffed animal in recent times ‚ÄĒ rescuing them from closets or shelves, gently stroking their much-repaired coat and reconnecting with ancient feelings of safety and innocence.

I spent 32 years living without Mister Rice Guy, because I made friends and gained confidence out in the world. But I had forgotten how to play.

We’ve all observed the intense absorption of children at play. As a writer, I’m envious of their ability to invent characters, storylines and games without effort. Imagination is a form of pleasure and escape. It’s not quite like an adult daydream. To play is to live in the present, unremittingly, without distraction or self-judgment. There’s a sense of discovery and wonder.

Playfulness is a collective trait. ‚ÄúI can walk into any daycare anywhere in this country and see children pretending all day long,‚ÄĚ says Taylor, who wrote the definitive book on pretend friends and has spent her career unraveling the mysteries of why we play. She believes the instinct for imaginary play is universal, and that imagination itself is fundamental to the human condition. And not just for humans. Taylor points to a handful of studies going back to the 1950s that suggest gorillas, chimpanzees and dolphins engage in imaginary play ‚ÄĒ among each other or with their human interlocutors.

The ‚Äúwhy‚ÄĚ of it is less evident: Play may serve a profound evolutionary purpose that we still don‚Äôt understand. But the capacity for imagination benefits us all our lives ‚ÄĒ whether it‚Äôs to propel us to the moon or to write the occasional poem. We also all have the capacity to think about things that don‚Äôt exist, might have been or could be. Thinking about the past, imagining a future: These are the tools of fiction. And what is our daily self-talk if not the adult version of our childhood attempts to cope with these past and future notions?

Who can we be speaking to?

Imaginary friendships weren’t even thought to be good for children until the 1990s, when an efflorescence of research began to suggest otherwise. Today, having fantasies of this nature is considered not just healthy, but an important rite of passage for some. Studies by Taylor and others suggest that up to 65 percent of us had an imaginary friend, or multiple friends, in childhood or adolescence. (Other studies suggest the number is much lower, around 30 percent).

Researchers have found that the presence of an imaginary friend ‚ÄĒ whether a wholly-invented figment of a child‚Äôs imagination or a favorite object like a stuffed animal that has a personality and ‚Äúconverses‚ÄĚ with the child ‚ÄĒ tends to correlate with high levels of creativity and empathy. Some of us invented entire worlds with imaginary characters and storylines, called paracosms. In doing so, we gained a whole lot more than companionship.

The benefits also accrue later in life. Several recent studies have shown the experience of having an imaginary companion likely makes adolescents and adults more independent, resilient and prone to ask for help when they need it. And, yes, adults who used to have imaginary friends do engage in more self-talk than other people.

But why might I ‚ÄĒ or any of us ‚ÄĒ seek a reunion with our pretend playmates? The answer may lie in the disorienting circumstances of our new reality. My childhood world was small and turbulent and vulnerable. Adults were the force majeure, compelling where I went and what I did. Our COVID-19 lives today are similarly proscribed, attenuated and disordered by forces outside our control. There‚Äôs a deadly pandemic on, and not even the grown-ups know what‚Äôs going to happen next. Our worlds are again defined by hard boundaries and closed doors. And just like in childhood, we survey our lives in the lonely hours of before-sleep or before-dawn, waiting for the point where we again have something to look forward to.

For me, spending time with Mister Rice Guy helped me realize how big my world truly is, no matter how small it can feel inside the daily closed loop of my pandemic bubble. The last time he and I played together when I was 8, his world was bounded by my green-carpeted bedroom and the fenced-in recess yard behind my school. When he came back to me, we enjoyed a leisurely ramble through the Sonoma County hills all day, hunted for ripe blackberries and compared the personalities of the different cows we ran into (and tried to run up to) on skinny ranchland trails.

After we took those first post-vaccination forays into the world, my fears started to ebb, and Mister Rice Guy stopped coming around. I‚Äôm OK with that ‚ÄĒ it was a reunion, after all, and this time his departure isn‚Äôt the sudden banishment of an ashamed 8-year-old girl. He‚Äôs gone away for now. But if living is coping with uncertainty, he could very well be back.

He’ll be welcome. I sleep better these days knowing I have an extra friend who requires no social distancing, who sees me clearly with his every-colored eyes. And who’ll remind me when it’s time to play.

Tags: childhood, COVID-19, Dr. Marjorie Taylor, Imaginary friends, Julia Scott, pandemic, Paracosms, The power of play

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

© 2026 Julia Scott.