Posts Tagged ‘New York Times Magazine’

A Wash On the Wild Side: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love My Microbiome

Sunday, May 25th, 2025

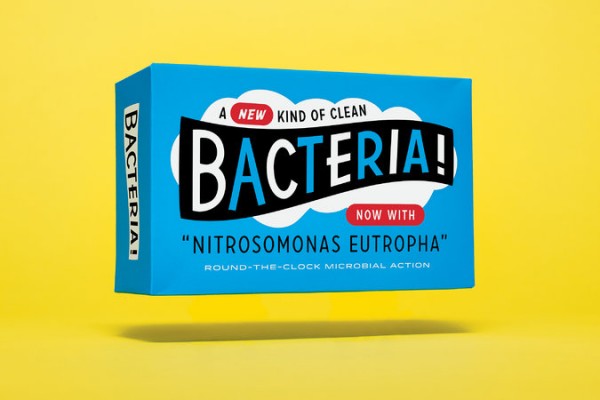

For most of my life, if I‚Äôve thought at all about the bacteria living on my skin, it has been while trying to scrub them away. But recently I spent four weeks rubbing them in. I was Subject 26 in testing a living bacterial skin tonic, developed by AOBiome, a biotech start-up in Cambridge, Mass. The tonic looks, feels and tastes like water, but each spray bottle of AO+ Refreshing Cosmetic Mist contains billions of cultivated Nitrosomonas eutropha, an ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) that is most commonly found in dirt and untreated water. AOBiome scientists hypothesize that it once lived happily on us too ‚ÄĒ before we started washing it away with soap and shampoo ‚ÄĒ acting as a built-in cleanser, deodorant, anti-inflammatory and immune booster by feeding on the ammonia in our sweat and converting it into nitrite and nitric oxide.

In the conference room of the cramped offices that the four-person AOBiome team rents at a start-up incubator, Spiros Jamas, the chief executive, handed me a chilled bottle of the solution from the refrigerator. ‚ÄúThese are AOB,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúThey‚Äôre very innocuous.‚ÄĚ Because the N. eutropha are alive, he said, they would need to be kept cold to remain stable. I would be required to mist my face, scalp and body with bacteria twice a day. I would be swabbed every week at a lab, and the samples would be analyzed to detect changes in my invisible microbial community.

In the last few years, the microbiome (sometimes referred to as ‚Äúthe second genome‚ÄĚ) has become a focus for the health conscious and for scientists alike. Studies like the Human Microbiome Project, a national enterprise to sequence bacterial DNA taken from 242 healthy Americans, have tagged 19 of our phyla (groupings of bacteria), each with thousands of distinct species. As Michael Pollan wrote in this magazine last year: ‚ÄúAs a civilization, we‚Äôve just spent the better part of a century doing our unwitting best to wreck the human-associated microbiota. . . . Whether any cures emerge from the exploration of the second genome, the implications of what has already been learned ‚ÄĒ for our sense of self, for our definition of health and for our attitude toward bacteria in general ‚ÄĒ are difficult to overstate.‚ÄĚ

While most microbiome studies have focused on the health implications of what‚Äôs found deep in the gut, companies like AOBiome are interested in how we can manipulate the hidden universe of organisms (bacteria, viruses and fungi) teeming throughout our glands, hair follicles and epidermis. They see long-term medical possibilities in the idea of adding skin bacteria instead of vanquishing them with antibacterials ‚ÄĒ the potential to change how we diagnose and treat serious skin ailments. But drug treatments require the approval of the Food and Drug Administration, an onerous and expensive process that can take upward of a decade. Instead, AOBiome‚Äôs founders introduced AO+ under the loosely regulated ‚Äúcosmetics‚ÄĚ umbrella as a way to release their skin tonic quickly. With luck, the sales revenue will help to finance their research into drug applications. ‚ÄúThe cosmetic route is the quickest,‚ÄĚ Jamas said. ‚ÄúThe other route is the hardest, the most expensive and the most rewarding.‚ÄĚ

AOBiome does not market its product as an alternative to conventional cleansers, but it notes that some regular users may find themselves less reliant on soaps, moisturizers and deodorants after as little as a month. Jamas, a quiet, serial entrepreneur with a doctorate in biotechnology, incorporated N. eutropha into his hygiene routine years ago; today he uses soap just twice a week. The chairman of the company‚Äôs board of directors, Jamie Heywood, lathers up once or twice a month and shampoos just three times a year. The most extreme case is David Whitlock, the M.I.T.-trained chemical engineer who invented AO+. He has not showered for the past 12 years. He occasionally takes a sponge bath to wash away grime but trusts his skin‚Äôs bacterial colony to do the rest. I met these men. I got close enough to shake their hands, engage in casual conversation and note that they in no way conveyed a sense of being ‚Äúunclean‚ÄĚ in either the visual or olfactory sense.

For my part in the AO+ study, I wanted to see what the bacteria could do quickly, and I wanted to cut down on variables, so I decided to sacrifice my own soaps, shampoo and deodorant while participating. I was determined to grow a garden of my own.

Week One

The story of AOBiome begins in 2001, in a patch of dirt on the floor of a Boston-area horse stable, where Whitlock was collecting soil samples. A few months before, an equestrienne he was dating asked him to answer a question she had long been curious about: Why did her horse like to roll in the dirt? Whitlock didn’t know, but he saw an opportunity to impress.

Whitlock thought about how much horses sweat in the summer. He wondered whether the animals managed their sweat by engaging in dirt bathing. Could there be a kind of ‚Äúgood‚ÄĚ bacteria in the dirt that fed off perspiration? He knew there was a class of bacteria that derive their energy from ammonia rather than from carbon and grew convinced that horses (and possibly other mammals that engage in dirt bathing) would be covered in them. ‚ÄúThe only way that horses could evolve this behavior was if they had substantial evolutionary benefits from it,‚ÄĚ he told me.

Whitlock gathered his samples and brought them back to his makeshift home laboratory, where he skimmed off the dirt and grew the bacteria in an ammonia solution (to simulate sweat). The strain that emerged as the hardiest was indeed an ammonia oxidizer: N. eutropha. Here was one way to test his ‚Äúclean dirt‚ÄĚ theory: Whitlock put the bacteria in water and dumped them onto his head and body.

Some skin bacteria species double every 20 minutes; ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are much slower, doubling only every 10 hours. They are delicate creatures, so Whitlock decided to avoid showering to simulate a pre-soap living condition. ‚ÄúI wasn‚Äôt sure what would happen,‚ÄĚ he said, ‚Äúbut I knew it would be good.‚ÄĚ

The bacteria thrived on Whitlock. AO+ was created using bacterial cultures from his skin.

And now the bacteria were on my skin.

I had warned my friends and co-workers about my experiment, and while there were plenty of jokes ‚ÄĒ someone left a stick of deodorant on my desk; people started referring to me as ‚ÄúTeen Spirit‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ when I pressed them to sniff me after a few soap-free days, no one could detect a difference. Aside from my increasingly greasy hair, the real changes were invisible. By the end of the week, Jamas was happy to see test results that showed the N. eutropha had begun to settle in, finding a friendly niche within my biome.

Week Two

AOBiome is not the first company to try to leverage emerging discoveries about the skin microbiome into topical products. The skin-care aisle at my drugstore had a moisturizer with a ‚Äúprobiotic complex,‚ÄĚ which contains an extract of Lactobacillus, species unknown. Online, companies offer face masks, creams and cleansers, capitalizing on the booming market in probiotic yogurts and nutritional supplements. There is even a ‚Äúfrozen yogurt‚ÄĚ body cleanser whose second ingredient is sodium lauryl sulfate, a potent detergent, so you can remove your healthy bacteria just as fast as you can grow them.

Audrey Gueniche, a project director in L‚ÄôOr√©al‚Äôs research and innovation division, said the recent skin microbiome craze ‚Äúhas revolutionized the way we study the skin and the results we look for.‚ÄĚ L‚ÄôOr√©al has patented several bacterial treatments for dry and sensitive skin, including Bifidobacterium longum extract, which it uses in a Lanc√īme product. Clinique sells a foundation with Lactobacillus ferment, and its parent company, Est√©e Lauder, holds a patent for skin application of Lactobacillus plantarum. But it‚Äôs unclear whether the probiotics in any of these products would actually have any effect on skin: Although a few studies have shown that Lactobacillus may reduce symptoms of eczema when taken orally, it does not live on the skin with any abundance, making it ‚Äúa curious place to start for a skin probiotic,‚ÄĚ said Michael Fischbach, a microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Extracts are not alive, so they won‚Äôt be colonizing anything.

To differentiate their product from others on the market, the makers of AO+ use the term ‚Äúprobiotics‚ÄĚ sparingly, preferring instead to refer to ‚Äúmicrobiomics.‚ÄĚ No matter what their marketing approach, at this stage the company is still in the process of defining itself. It doesn‚Äôt help that the F.D.A. has no regulatory definition for ‚Äúprobiotic‚ÄĚ and has never approved such a product for therapeutic use. ‚ÄúThe skin microbiome is the wild frontier,‚ÄĚ Fischbach told me. ‚ÄúWe know very little about what goes wrong when things go wrong and whether fixing the bacterial community is going to fix any real problems.‚ÄĚ

I didn’t really grasp how much was yet unknown until I received my skin swab results from Week 2. My overall bacterial landscape was consistent with the majority of Americans’: Most of my bacteria fell into the genera Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus, which are among the most common groups. (S. epidermidis is one of several Staphylococcus species that reside on the skin without harming it.) But my test results also showed hundreds of unknown bacterial strains that simply haven’t been classified yet.

Meanwhile, I began to regret my decision to use AO+ as a replacement for soap and shampoo. People began asking if I‚Äôd ‚Äúdone something new‚ÄĚ with my hair, which turned a full shade darker for being coated in oil that my scalp wouldn‚Äôt stop producing. I slept with a towel over my pillow and found myself avoiding parties and public events. Mortified by my body odor, I kept my arms pinned to my sides, unless someone volunteered to smell my armpit. One friend detected the smell of onions. Another caught a whiff of ‚Äúpleasant pot.‚ÄĚ

When I visited the gym, I followed AOBiome’s instructions, misting myself before leaving the house and again when I came home. The results: After letting the spray dry on my skin, I smelled better. Not odorless, but not as bad as I would have ordinarily. And, oddly, my feet didn’t smell at all.

Week Three

My skin began to change for the better. It actually became softer and smoother, rather than dry and flaky, as though a sauna‚Äôs worth of humidity had penetrated my winter-hardened shell. And my complexion, prone to hormone-related breakouts, was clear. For the first time ever, my pores seemed to shrink. As I took my morning ‚Äúshower‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ a three-minute rinse in a bathroom devoid of hygiene products ‚ÄĒ I remembered all the antibiotics I took as a teenager to quell my acne. How funny it would be if adding bacteria were the answer all along.

Dr. Elizabeth Grice, an assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania who studies the role of microbiota in wound healing and inflammatory skin disease, said she believed that discoveries about the second genome might one day not only revolutionize treatments for acne but also ‚ÄĒ as AOBiome and its biotech peers hope ‚ÄĒ help us diagnose and cure disease, heal severe lesions and more. Those with wounds that fail to respond to antibiotics could receive a probiotic cocktail adapted to fight the specific strain of infecting bacteria. Body odor could be altered to repel insects and thereby fight malaria and dengue fever. And eczema and other chronic inflammatory disorders could be ameliorated.

According to Julie Segre, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute and a specialist on the skin microbiome, there is a strong correlation between eczema flare-ups and the colonization of Staphylococcus aureus on the skin. Segre told me that scientists don‚Äôt know what triggers the bacterial bloom. But if an eczema patient could monitor their microbes in real time, they could lessen flare-ups. ‚ÄúJust like someone who has diabetes is checking their blood-sugar levels, a kid who had eczema would be checking their microbial-diversity levels by swabbing their skin,‚ÄĚ Segre said.

AOBiome says its early research seems to hold promise. In-house lab results show that AOB activates enough acidified nitrite to diminish the dangerous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A regime of concentrated AO+ caused a hundredfold decrease of Propionibacterium acnes, often blamed for acne breakouts. And the company says that diabetic mice with skin wounds heal more quickly after two weeks of treatment with a formulation of AOB.

Soon, AOBiome will file an Investigational New Drug Application with the F.D.A. to request permission to test more concentrated forms of AOB for the treatment of diabetic ulcers and other dermatologic conditions. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs very, very easy to make a quack therapy; to put together a bunch of biological links to convince someone that something‚Äôs true,‚ÄĚ Heywood said. ‚ÄúWhat would hurt us is trying to sell anything ahead of the data.‚ÄĚ

Week Four

As my experiment drew to a close, I found myself reluctant to return to my old routine of daily shampooing and face treatments. A month earlier, I packed all my hygiene products into a cooler and hid it away. On the last day of the experiment, I opened it up, wrinkling my nose at the chemical odor. Almost everything in the cooler was a synthesized liquid surfactant, with lab-manufactured ingredients engineered to smell good and add moisture to replace the oils they washed away. I asked AOBiome which of my products was the biggest threat to the ‚Äúgood‚ÄĚ bacteria on my skin. The answer was equivocal: Sodium lauryl sulfate, the first ingredient in many shampoos, may be the deadliest to N. eutropha, but nearly all common liquid cleansers remove at least some of the bacteria. Antibacterial soaps are most likely the worst culprits, but even soaps made with only vegetable oils or animal fats strip the skin of AOB.

Bar soaps don‚Äôt need bacteria-killing preservatives the way liquid soaps do, but they are more concentrated and more alkaline, whereas liquid soaps are often milder and closer to the natural pH of skin. Which is better for our bacteria? ‚ÄúThe short answer is, we don‚Äôt know,‚ÄĚ said Dr. Larry Weiss, founder of CleanWell, a botanical-cleanser manufacturer. Weiss is helping AOBiome put together a list of ‚Äúbacteria-safe‚ÄĚ cleansers based on lab testing. In the end, I tipped most of my products into the trash and purchased a basic soap and a fragrance-free shampoo with a short list of easily pronounceable ingredients. Then I enjoyed a very long shower, hoping my robust biofilm would hang on tight.

One week after the end of the experiment, though, a final skin swab found almost no evidence of N. eutropha anywhere on my skin. It had taken me a month to coax a new colony of bacteria onto my body. It took me three showers to extirpate it. Billions of bacteria, and they had disappeared as invisibly as they arrived. I had come to think of them as ‚Äúmine,‚ÄĚ and yet I had evicted them.

– – –

BONUS: Eavesdrop on Julia’s conversation with The 6th Floor blog at the New York Times.

Tags: AOBiome, Bacteria, Bacteria skin spray, Julia Scott, Julie Segre, Lactobacillus, Michael Fischbach, New York Times Magazine, Nitrosomonas Eutropha, No poo, Probiotic cleanser, Probiotic cosmetics, Probiotic FDA regulation, Probiotics, Skin microbiome, Sodium laurel sulfate

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

The Loneliest Man in Belize

Thursday, May 1st, 2025

‘Rozco! Love you, hon!‚ÄĚ cried a man in baggy jeans. His shout, insincere and taunting, was aimed at the back of Caleb Orozco, a 41-year-old man walking along a row of tarp-covered souvenir stands near one of Belize City‚Äôs ferry terminals. Orozco‚Äôs only acknowledgment was to walk a little faster, car keys clutched in his hand. It was a hot December afternoon, a week before Christmas, high season in the city‚Äôs tourist zone. Two policemen appraised Orozco but said nothing as more taunts flew. ‚ÄúSaw you on TV!‚ÄĚ a woman dressed in white jeered from her craft stand, where she sold carved wooden boats. Farther down the sidewalk, two men snickered. ‚ÄúCaleb! You done rub too hard!‚ÄĚ leered a man in a blue baseball cap, pointing to Orozco‚Äôs crotch.

‚ÄúBatiman!‚ÄĚ someone called from the shade of a food¬≠-cart umbrella.

In Belize ‚ÄĒ a small Anglophone Caribbean nation tucked into the eastern flank of Guatemala and Mexico ‚ÄĒ ‚Äúbatiman‚ÄĚ (Creole for, literally, ‚Äúbutt man‚ÄĚ) has long been the supreme slur against gay men, the worst possible insult to their personhood and dignity. But now another slur is beginning to take its place: ‚ÄúOrozco.‚ÄĚ

Five years ago, Orozco‚Äôs lawyer walked into the Belize Supreme Court Registry and handed over a stack of papers that initiated the first challenge in Caribbean history to the criminalization of sodomy. Caleb Orozco v. the Attorney General of Belize focuses on Section 53, a statute in the Belize criminal code that calls for a 10-year prison term for ‚Äúcarnal intercourse against the order of nature.‚ÄĚ If Orozco won, his supporters hoped, it would establish a moral precedent across the Caribbean and even create a domino effect, putting pressure on other governments to decriminalize sodomy. But it took three years for the Supreme Court to hear the case; two years later, the nation still awaits a verdict.

In the meantime, Orozco operates the United Belize Advocacy Movement, or Unibam, the only gay ¬≠rights advocacy and policy group in Belize, out of his home in a thick-walled compound on Zericote Street, where stray dogs nose for food scraps in the dirt. The walls are topped with broken shards of glass and rusty, upside-down nails. A seven-foot-tall security gate barricades his driveway. When home, he must remember to lock all six locks ‚ÄĒ two for his house, two for his office and two padlocks on the gate for good measure. Those precautions do not prevent Orozco‚Äôs neighbor or people walking by his house from throwing rocks and bottles over the walls, shouting, ‚ÄúAala unu fu ded‚ÄĚ (‚ÄúAll of you should die‚ÄĚ). Other residents have picked up two-¬≠by-fours and chased him in the street. People stone Orozco‚Äôs house frequently enough that he rarely bothers to call the police at this point. (This being Belize, a country with a population of just 360,000, he sometimes knows whoever is throwing the rocks on Zericote Street anyway.)

Orozco‚Äôs natural habitat, the place where he feels powerful and at ease, is in front of his pink laptop in his office, a squat outbuilding with barred windows. Inside these walls, no one will disparage his manner of dress: snug graphic tee, stylish camo-print shorts and black Keds that hug his feet like shapely hooves. No one will comment on the way he styles his hank of hair, with a flip to the left and some highlights that tend to come out looking gray. He greets clients and funders with a soft handshake and a wry joke ‚ÄĒ usually at his own expense. When they leave, he spends hours online in the growing dark, sometimes past midnight.

‚ÄúDid you know we caused the floods in Belize?‚ÄĚ he remarked airily, scrolling through headlines on a local news site. ‚ÄúThere‚Äôs an actual comment from a man who says so.‚ÄĚ Later he double-¬≠locked his office doors and led the way across a yard strung with empty clothing lines, dry grass crackling underfoot. He paused for a few moments, listening for unrest from his neighbor‚Äôs house, before mounting the heavily sagging steps. He jerked open the sticky door. The floor tipped at an angle, and the ceiling was patched and moldy. One window had holes big enough for him to poke his head through. ‚ÄúMy house is like my life ‚ÄĒ a hot mess,‚ÄĚ he said, making his favorite joke with a wan smile.

He is Belize’s most reviled homosexual and its most ostracized citizen, a man whom fundamentalists pray for and passers-by scorn; a marked man at 30 paces. His weary face is on the evening news and in newspaper caricatures, which have depicted him in fishnets and heels. His name is now a label, one used to remind other gays that they are sinners and public offenders. Win or lose, Orozco’s fight for his fundamental rights and freedoms will follow him for the rest of his life.

Americans and Europeans visit Belize for all the things that make ‚Äúthe Jewel‚ÄĚ an ideal place to relax: coral reefs, paradisiacal white beaches, a green-azure sea. It is a deeply Christian country, with a Constitution that proclaims the ‚Äúsupremacy of God‚ÄĚ as a first principle. Recently, it has seen a surge in Pentecostalism and other proselytizing strains of faith. Although bounded on two sides by Latin American countries with more liberal attitudes toward same-sex relationships, Belize retains a culture more closely aligned with Caribbean countries whose perspectives were colored by 200 years of British occupation. There is an ethos of ‚Äúlive and let live,‚ÄĚ but only as long as the gay community remains invisible. Gay couples cohabitate and quietly raise children, but without demanding legal recognition. Couples don‚Äôt hold hands in public. No hate-crime laws exist to punish targeted assaults.

Formerly British Honduras, Belize gained independence in 1981, inheriting most of its governing documents from its former master. Section 53 is an artifact of Belize‚Äôs colonial past dating to the 1880s. The British bequeathed similar ‚Äúbuggery‚ÄĚ laws to all 11 other Caribbean countries once ruled by the crown. (The Bahamas has subsequently removed them.) Buggery became a criminal offense in the England of King Henry VIII in 1533. Of the 76 countries that still criminalize sodomy around the world today, most do so as a holdover from British colonial rule. (Britain repealed its buggery laws in 2003.) In Belize, anti¬≠gay laws extend beyond the criminal code: Homosexuals are still technically an explicit class of prohibited immigrants, along with prostitutes, ‚Äúany idiot,‚ÄĚ the insane and ‚Äúany person who is deaf and dumb.‚ÄĚ

Much as with Lawrence v. Texas, the case whose resolution in the United States Supreme Court invalidated anti-¬≠sodomy laws still on the books in 13 states, Orozco‚Äôs challenge is less about sodomy than about discrimination. Even the most zealous Christian leaders, the ones leading the crusade to keep Section 53 on the books, acknowledge that law or no law, sodomy does happen in the privacy of bedrooms in Belize ‚ÄĒ and not just between gay men, either. Despite the fact that the law is rarely enforced, Orozco and his lawyers say that the threat of indictment encourages public harassment, threats and occasional violence against many gays and lesbians, who have little recourse. The police sometimes charge hush money not to turn people in, according to Lisa Shoman, one of Orozco‚Äôs attorneys. The Belize attorney general told me that he personally believes that Section 53 is discriminatory, though his office is obligated to defend it in court.

Orozco is an unlikely instigator of this challenge. He wasn‚Äôt politically galvanized until he was 31, when he went to a workshop for gay men and people living with H.I.V. at a public health conference in Belize City. One by one, the men stood up, spoke their names and added, ‚ÄúI have H.I.V.‚ÄĚ or ‚ÄúI have sex with men.‚ÄĚ Orozco was bowled over. ‚ÄúI got up and said, ‚ÄėBy the way, I like men.‚Äô I realized that you perpetuate your own mistreatment by remaining silent. And I decided I would not be silent anymore.‚ÄĚ

A year later, he helped found Unibam as a public-¬≠health advocacy group for gay men. Until that point, Orozco had never paid much attention to the H.I.V. epidemic in his country. Even after one of his uncles, who was gay, died from complications related to AIDS, Orozco didn‚Äôt fully grasp what had killed him. He couldn‚Äôt acknowledge being gay ‚ÄĒ to others or himself ‚ÄĒ until well into his college years. ‚ÄúPeople would ask me, ‚ÄėAre you gay?‚Äô And I would say stupid things like: ‚ÄėI‚Äôm trisexual. I‚Äôll try anything just once,‚Äô‚ÄČ‚ÄĚ he recalled. ‚ÄúThe truth was, I wouldn‚Äôt try anything.‚ÄĚ He didn‚Äôt have sex until he was 23, and when he did, he felt pressured into it. He has never had a long-¬≠term boyfriend. The men Orozco knows won‚Äôt be seen with him. ‚ÄúThere was one man who would only want me to pick him up after 8 o‚Äôclock at night,‚ÄĚ he said, rolling his eyes. ‚ÄúI think about it all the time ‚ÄĒ is this the price I‚Äôm paying? To have no love life? To be the one publicly gay man in Belize? To be the most socially isolated?‚ÄĚ

Orozco did not have litigation on his mind at an H.I.V. conference in Jamaica in 2009 when he spoke to two law professors ‚ÄĒ one Jamaican, one Guyanese ‚ÄĒ with the University of the West Indies Rights Advocacy Project, which they had recently founded with a colleague to focus on human rights in the Caribbean. They had been studying bans on same-¬≠sex relationships, laying the groundwork for a test case that, if successful, could encourage similar legal challenges in neighboring countries. Belize was ideal: It had a Constitution with stronger personal privacy and equality protections than other Caribbean countries. From a human rights point of view, it was a case they thought they could win.

When Orozco heard this, he recalled, ‚ÄúI put up my hand ‚ÄĒ literally ‚ÄĒ and said: ‚ÄėWhat about me? I‚Äôm ready since yesterday. How can we do this?‚Äô‚ÄČ‚ÄĚ But even as he signed the legal papers, litigation itself was never the point. ‚ÄúI realized the case was simply a tool to create a national dialogue,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúIt isn‚Äôt just Section 53. It‚Äôs adoption. It‚Äôs Social Security. It‚Äôs not having the first say of the health of your partner. There‚Äôs the dignity issues, which haven‚Äôt been recognized.‚ÄĚ

The legal challenge was a controversial move in Belize‚Äôs gay community, where the question of gay rights ‚ÄĒ what they are and how to get them ‚ÄĒ is a conversation that has just barely begun. Belize has never had an inciting incident to catalyze a movement, like the 1969 Stonewall uprising. There is no annual Gay Pride parade. No member of government or other prominent figure has ever come out. No gay bars or ritual ‚Äúsafe spaces‚ÄĚ exist as places for people to meet, just carefully organized house parties and private encounters on Facebook. The L.G.B.T. community in Belize, with the exception of a dedicated corps of organizers and supporters, remains timid, fractured and apolitical. Unibam itself has only 128 members, in part because of people‚Äôs concern that their names could be made public. ‚ÄúDon‚Äôt ask, don‚Äôt tell ‚ÄĒ that‚Äôs the way with just about everything here,‚ÄĚ said Kelvin Ramnarace, a Unibam board member. ‚ÄúIt doesn‚Äôt mean progress. It‚Äôs one thing to not have rights and know it. Here you think you do, because it‚Äôs not so hard to live here. But we don‚Äôt.‚ÄĚ

But Orozco’s lawyers had reasons to hope that a softening was at hand. The tone had already begun to shift across much of neighboring Latin America, where activists were laying the groundwork for a string of victories. Today, six Latin American countries recognize same-­sex marriage or civil unions. Eleven countries have banned employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and seven countries protect L.G.B.T. citizens against hate crimes.

‚ÄúEven though people said they anticipated some backlash in Belize, almost all the groups I spoke to seemed favorable,‚ÄĚ said Arif Bulkan, the Guyanese lawyer Orozco met at the H.I.V. conference. Bulkan and his colleagues spoke to a range of Belizean civil-¬≠society groups and local leaders, including those in the church establishment. He recalled an important meeting with the president, at the time, of the Belize Council of Churches, which encompasses Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Methodists and Presbyterians. ‚ÄúHe said they wouldn‚Äôt support us openly,‚ÄĚ Bulkan said, ‚Äúbut they wouldn‚Äôt oppose us either.‚ÄĚ

So Orozco had few reasons to think he might regret putting his reputation, and Unibam‚Äôs, on the line. Today, he shakes his head like a man in a dream. ‚ÄúI just thought it was going to be some litigation,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúI didn‚Äôt expect opponents, didn‚Äôt expect propaganda and all that other stuff that happened.‚ÄĚ He paused. ‚ÄúI really didn‚Äôt.‚ÄĚ

In Belize, church leaders are granted deference in the press and by lawmakers on social issues. But in large part, the ecclesiastical focus has always been on the spiritual rather than the political realm. So Orozco was blindsided by the announcement, soon after the suit was filed, that the Roman Catholic Church of Belize, the Belize Evangelical Association of Churches and the Anglican Church had together joined the case on the government‚Äôs side as an ‚Äúinterested party,‚ÄĚ a legal distinction that allowed them to hire lawyers, file motions and be heard during the trial. More than 400 church leaders and ministries came together to mobilize their adherents in the name of public morality. In another first for Belize, church leaders founded a nationwide activist campaign, Belize Action, and began drawing thousands of believers to rallies that denounced the ‚Äúhomosexual agenda.‚ÄĚ

The churches also flexed their legal muscle in a pretrial motion to remove Unibam as a claimant in the case; as an organization, they argued, it had no standing to challenge the law. Their motion succeeded. Suddenly Orozco was the sole claimant. The case would come down to whether Orozco‚Äôs personal human rights had been violated. He was hounded for interviews, and his name was broadcast all over the world. Someone posted a video to YouTube called ‚Äú[Expletive] Unibam dis da Belize,‚ÄĚ with a photo of Orozco. He received death threats when his name was printed. Shoman, an opposition senator in the National Assembly of Belize as well as one of his lawyers, received explicit rape threats. One day, Orozco was walking downtown, alone, when a man on a bicycle, shouting antigay slurs, threw an empty beer bottle at Orozco‚Äôs head. It smacked him on the jaw and cracked two of his molars. After taking his statement, ‚Äúthe police said, ‚ÄėIf you find who did this, tell us, and we will pick them up.‚Äô Why is that my responsibility?‚ÄĚ he asked me with a sardonic smile.

Before the churches joined the case, Orozco allowed three organizations to join forces as an interested party on his side: the Commonwealth Lawyers Association, the International Commission of Jurists and the Human Dignity Trust, major transnational nongovernmental organizations with global standing, large budgets and access to the best human ¬≠rights lawyers in the world. ‚ÄúI thought that using interested parties from the international community would have brought some kind of leverage,‚ÄĚ he told me.

But the presence of these foreign groups, even on paper, allowed Orozco‚Äôs enemies to reframe the case as an act of cultural aggression by the global north. According to Bulkan, ‚Äúa lot of the negative press after that was about foreigners coming in.‚ÄĚ Prime Minister Dean Barrow told a local news station: ‚ÄúOne of the things that we have to be grateful for in this country is the culture wars we see in the United States have not been imported into Belize. Well, obviously, this is the start of exactly such a phenomenon.‚ÄĚ The United States and Europe were meddling colonizers, Orozco their traitorous pawn. Orozco‚Äôs religious opponents referred to victories for same-¬≠sex marriage in California and Canada as further evidence of the true agenda at work in Belize. ‚ÄúIt puts a lot of pressure on us,‚ÄĚ Orozco said. ‚ÄúWhen we started this, we weren‚Äôt thinking about gay marriage.‚ÄĚ

Opponents made much of the fact that Unibam receives all of its budget, around $35,000 a year, from foreign governments and foundations, including the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives, the Swiss Embassy in Mexico City and the Open Society Foundations. ‚ÄúIs Unibam being used for a foreign gay agenda?‚ÄĚ one news station asked. The Amandala, the nation‚Äôs largest newspaper, published a page-¬≠long editorial under the headline ‚ÄúUNIBAM DIVIDES BELIZE.‚ÄĚ ‚ÄúHomosexuals are predators of young and teenaged boys,‚ÄĚ wrote the editor in chief, Russell Vellos, in a separate column. ‚ÄúWoe unto us, Belize, if homosexuals are successful in our court. Woe unto us! In fact, since ours is a ‚Äėtest case,‚Äô woe unto the world!‚ÄĚ

Six days a week, Orozco drives to his mother‚Äôs squat rental in a Belize City suburb and sits down at her glass kitchen table. Perla Ozeata, a matter-¬≠of-fact woman with the same dark eyes as her son‚Äôs, serves up his favorites: steaming dark bowls of chimole, a Belizean specialty; escabeche with chicken and whole jalape√Īos; and her special cheesecake. Strangers have cursed her for ‚Äúencouraging‚ÄĚ her son to be gay, but she is proud of him. The first day Orozco went to court, he wore clothes his mother bought him. She ironed his shirt and tied his tie. Sometimes when she looks at him, she still sees the friendless schoolboy who played in the yard by himself, catching lizards and trying to avoid his bullies and his father‚Äôs chronic disapproval. She intends to one day tear down the house on Zericote Street and rebuild, so she can move back in with him and protect him. ‚ÄúSomebody have to live with Caleb, because people take advantage of him,‚ÄĚ she told me one afternoon. ‚ÄúCaleb no fighter. He can fight out the mouth, but he can‚Äôt fight physical.‚ÄĚ At one point, when Orozco was out of earshot, she said in a low voice: ‚ÄúEvery time he walk the street, they promise to kill him. Win or lose the case, they‚Äôll kill him.‚ÄĚ

These days Orozco leaves his compound on foot for only two reasons: to walk to the bank (10 minutes) or to the market for groceries (five minutes). On good days, he can make the 10-minute walk in seven and the five-minute one in three. But even inside a place of commerce, things can go awry. ‚ÄúA gentleman said he wanted to push his bat up my you-¬≠know-¬≠what,‚ÄĚ Orozco told me at one point. ‚ÄúI was at the bank. I had my nieces with me.‚ÄĚ

He was sitting on his messy bed, his knees pressed together. His clothes were jammed into a dresser decorated with peeling children‚Äôs stickers. Twice a day, Orozco brushes his teeth over the tub because he doesn‚Äôt have a sink. The walls are a single run of wooden slats with holes like gapped teeth, so pests are a problem. ‚ÄúCompare rats to spiders, and I prefer spiders,‚ÄĚ he said.

Coming out is supposed to broaden your world. Orozco‚Äôs world has narrowed to the space between these walls. Some days the tension in his neck hurts so badly that he resorts to painkillers. Other days he just feels numb. He doesn‚Äôt answer his cellphone when it rings and just watches TV until he drops off to sleep. ‚ÄúI don‚Äôt like feeling trapped,‚ÄĚ he acknowledged. ‚ÄúBut I cannot afford to lose myself in this work. I create my own social space, completely.‚ÄĚ

Once in a while he takes a chance on a night out at Dino‚Äôs, a dance club in downtown Belize City. But he never goes without a friend. At midnight one Saturday, Orozco parked near a faded billboard with a picture of a sad-looking woman and the message ‚ÄúABORTION: ONE DEAD, ONE WOUNDED.‚ÄĚ With his sister Golda, her husband and a friend, he ascended a narrow concrete stairwell to a long, dark room with earsplitting Caribbean dance music. ‚ÄúThis is what we do,‚ÄĚ Orozco said, shrugging. It‚Äôs an in-¬≠joke that Belize City‚Äôs only gay-friendly club is on Queen Street. Drag queens have performed as dancers and singers, but on most nights, like the night we visited, the club is filled with straight couples grinding up against the plywood walls. ‚ÄúNot a lot of gays here,‚ÄĚ I said. Orozco replied, ‚ÄúThat‚Äôs the challenge.‚ÄĚ

There were a lot of watchful eyes at Dino’s. Camo-clad security guards, grim-faced and armed, scanned the crowd for troublemakers. Hand-painted brontosaurs and stegosauri stared out from the walls, rendered with cartoon menace in Day-­Glo colors under black light. As the dancers watched one another, they took in Orozco, taller than most Belizean men at 5-foot-11, as he stood by the door for a long time in burnt-­orange slacks and natty brogues, sipping a Coke over ice. He watched them back, seeming very ill at ease.

Orozco counted eight members of his tribe in the room that night. He knew all their names, professions and stories. But in four hours, only one, a contractor who had done some work with Unibam, approached Orozco and his group to say hello. Orozco approached no one at all. ‚ÄúI don‚Äôt have many friends,‚ÄĚ he acknowledged later on. ‚ÄúYou turn left, you have criticism. You turn right, you have indifference.‚ÄĚ He has warm relationships with his clients and colleagues, but he doesn‚Äôt socialize.

Ramnarace, the Unibam board member, told me that he supports Orozco as a leader, but that others in the gay community have their doubts. ‚ÄúInternationally, I think he is more accepted than he is locally,‚ÄĚ Ramnarace said. ‚ÄúBecause when he says certain things here, he doesn‚Äôt always come across well.‚ÄĚ In interviews, Orozco can appear peevish or overly cerebral, seeming impatient with his interviewer or else resorting to the programmatic lexicon he uses at human rights meetings. ‚ÄúBut still,‚ÄĚ Ramnarace went on, ‚Äúhe‚Äôs a brave little bitch to go do that, even to fumble. It isn‚Äôt easy to do, not here, not alone, a little Hispanic guy.‚ÄĚ

Orozco used to love going out dancing late at night. One memorable time at Dino‚Äôs, he made out with a man in public, right there on the dance floor. Tonight, he and his small group formed a circle in the darkest part of the room. Golda began to dance in her gold sandals and light flowered dress, smiling at her older brother in an encouraging way. Her husband and their friend danced at her sides. Orozco, expressionless, planted himself near a pillar and began moving in place, gazing down at the floor. ‚ÄúAs long as I don‚Äôt see an eye looking at me, I can lose myself in the music,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúI just don‚Äôt want to be conscious of anyone‚Äôs eyes looking at me.‚ÄĚ

It has now been 24 months since the hearings on Section 53, with no word on when Chief Justice Kenneth Benjamin will deliver a decision. The Supreme Court does not have a calendar for decisions, and sources close to the case have refused to speculate as to the cause of the unusual delay. The Supreme Court Registry did not answer a request for comment. ‚ÄúUnfortunately, civil matters in this country do proceed at a very slow pace,‚ÄĚ Shoman said. ‚ÄúBut I could never have imagined that something of this magnitude, a case regarding the personal liberty of the citizens, should take so long.‚ÄĚ She and the rest of Orozco‚Äôs legal team have sent multiple letters to the registrar general but received no reply.

Jonathan Cooper, the chief executive of the Human Dignity Trust, is just as eager for results. ‚ÄúThe ramification of the Belize decision will be felt across the Commonwealth, if not beyond,‚ÄĚ he told me. Because either side is likely to appeal any decision all the way to the Caribbean Court of Justice, the highest court for not only Belize but also Barbados, Dominica and Guyana, the controversy (and Orozco‚Äôs notoriety) is likely to spill over into those nations as well. And then there is the matter of international human rights law. The legal groups invoked the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights in their argument, with the knowledge that should the appeals court rule in Orozco‚Äôs favor on that basis, other jurisdictions would find the criminalization of sodomy very hard to justify.

After waiting so many years, Orozco has made a decision of his own. Shortly after the court hearings, he quietly stepped down as the president of Unibam. He stayed on as its executive director, but he told me that he hopes to leave that post next year. ‚ÄúI‚Äôve come to realize that I‚Äôve sacrificed my life to this work,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúAnd I wake up to an empty bed and a pillow. And what does that say about me?‚ÄĚ

These are not the words of a Harvey Milk revolutionary, and in fact Orozco doesn‚Äôt see himself in the mold of Milk, who was murdered at 48. But Orozco has believed for some time now that he won‚Äôt outlive his middle age. ‚ÄúMy larger goal is to survive to the end of my case,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúThey said that if something should happen to me, the case would be over. I‚Äôve invested seven years of my life in this thing, and I don‚Äôt want to throw that away.‚ÄĚ

Orozco has come to the conclusion that the big changes he thought were within reach five years ago are actually a generation away. Living in Belize as a gay man or woman is like peering across a demilitarized zone with a pair of binoculars. If he took a four-¬≠hour bus ride to Chetumal, Mexico, Orozco would enjoy the right to marry. Someday, Orozco may tear down his house and rebuild it. He may go to law school or pick up the business-administration career he left behind. But he has ruled out leaving Belize. He loves his family too much. He hopes that with time, most of his fellow Belizeans will learn not to judge. ‚ÄúOur opponents have been fear-mongering,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúMost people could care less what I do in my bedroom.‚ÄĚ

One afternoon, Orozco took his least favorite walk, to the bank. He rose from his office chair, turned off the fan, cut the lights, locked all six locks and stepped out in a brown tie-dye button-down and knee­-length cotton pinstripe shorts. The narrow downtown streets were clogged with cars short on mufflers, long on horns. He passed bakeries and pharmacies and street vendors hawking bags of peanuts and dried fruit and discount clothing stores blaring pop music.

Stoop-¬≠sitters on Central American Boulevard nudged one another and gestured. A man in a truck driver‚Äôs uniform, smoking a cigarette, quietly watched Orozco go by, then spat and uttered a profanity. Two adolescent girls turned to look back at his retreating form, then doubled over with laughter. Three construction workers, legs dangling in a muddy trench, looked up as Orozco walked past. ‚ÄúHey, Belize bwai!‚ÄĚ they shouted. ‚ÄúHoo da fayri, butt bwai?‚ÄĚ

A few steps from the bank, Orozco passed two women alongside a young girl with her hair tied back in braids, wearing gold sandals and a flouncy white dress. She gazed at Orozco with curiosity. Then she looked up. ‚ÄúMama,‚ÄĚ she said, ‚Äúthat‚Äôs a batiman.‚ÄĚ

Tags: anti-gay, Belize, Belize Action, Belizean, buggery, Caleb Orozco, Caribbean Court of Justice, Caribbean gay rights, gay and lesbian, Julia Scott, LGBT, New York Times Magazine, Scott Stirm, section 53, sodomy law, Unibam

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

Letter of Recommendation: Candle Hour

Tuesday, March 18th, 2025

One of my best teenage memories starts with a natural disaster. In January 1998, my parents and I returned to our home in Montreal to find that a giant tree limb had ruptured our living room. What would soon be known as the Great Quebec Ice Storm had struck. It was the most catastrophic in modern Canadian history. Accumulations of freezing rain had cracked our maple tree nearly in half. It shattered our front window, glass fringing the tree limb like a body outline in a murder scene.

Outside, downed power lines sparked like electric snakes. More than a million Quebecers were left without power. Cars were crushed and impaled by fallen limbs. Because the ice could inflict violence at any moment, everyone retreated indoors, making for an oddly quiet state of emergency. Except for the distant beeps of electrical-crew trucks, all you could hear was the crack of trees buckling under the weight of the ice, day and night. Long after the sidewalks were cleared, we tiptoed past the eaves of tall buildings and kept our voices low, steering clear of icicles thick as baseball bats and sharp as spikes, primed to fall at any moment.

For seven days and seven nights, until the power returned, we lived by candlelight. We learned to be mindful of candles: how to stand them up, walk with them, nurture their light. At first it was maddening to cook dinner ‚ÄĒ to carefully carry a plate of candles to the cupboard, poke around for ingredients, then go off again in search of a knife, taking care not to drip wax into the cutlery drawer. I learned how to brush my teeth and bathe by candlelight; the light bounced off the mirrors, making the bathroom for once the brightest room in the house. In our bedrooms, we piled under blankets and read ourselves to sleep by the flickering flames.

Outside, our neighborhood descended into darkness at twilight, but if I stared hard enough at windows blurred with ice, I could just make out little dancing lights. Decades later, no one in my family remembers what we talked about, or ate, or how we spent our afternoons that week. But we all remember the candles.

The Montreal Ice Storm, 1998. (Archives de Montreal)

I’ve since settled in California, and last January events in the world left me with a hunger for silence. I adopted a strict information diet: no television news or social media. One evening, I didn’t even bother to flick on the lights in my apartment. I walked quietly to the window and watched the last of the day, the darkness swallowing the trees along my street. Instinctively, I went looking for a book of matches in the back of the kitchen junk drawer. Opening a closet, I felt around until I discovered the remnant of a housewarming gift: a milk-white candle. I struck a match and lit the dusty wick. I commandeered a plate from the cupboard and set it on my coffee table. I nestled in a blanket, listening to the wind in the courtyard. Eventually, for the first time in too many days, I found myself surrendering to sleep.

That was the start of a practice I‚Äôve taken to calling Candle Hour. An hour before I go to bed, I turn off all my devices for the night. I hit the lights. I light a candle or two or three ‚ÄĒ enough to read a book by, or to just sit and stare at the flame, which, by drawing oxygen, reminds me I need to breathe, too. I surround myself with scents and objects I like ‚ÄĒ some fresh rosemary plucked from a neighbor‚Äôs bush, a jar of redwood seed pods. I have a journal ready, but I don‚Äôt pressure myself to write in it. Candle Hour doesn‚Äôt even need to last a full hour, though; sometimes it lasts far longer. I sit until I feel an uncoupling from the chaos, or until the candle burns all the way down, or sometimes both.

Candle Hour has become a soul-level bulwark against so many different kinds of darkness. I feel myself slipping not just out of my day but out of time itself. I shunt aside outrages and anxieties. I find the less conditional, more indomitable version of myself. It’s that version I send into my dreams.

At night, by candlelight, the world feels enduring, ancient and slow. To sit and stare at a candle is to drop through a portal to a time when firelight was the alpha and omega of our days. We are evolved for the task of living by candlelight and maladapted to living the way we live now. Studies have noted the disruptive effects of nighttime exposure to blue-spectrum light ‚ÄĒ the sort emanated by our devices ‚ÄĒ on the human circadian rhythm. The screens trick us into thinking we need to stay alert, because our brains register their wavelength as they would the approach of daylight. But light on the red end of the spectrum sends a much weaker signal. In the long era of fire and candlelight, our bodies were unconfused as they began to uncoil.

Tonight‚Äôs candlelight will cast the same glow on my Oakland walls as it did on my parents‚Äô walls in Montreal in 1998. I‚Äôll feel in my bones that the day has passed ‚ÄĒ as all days, even fearful ones, eventually do. The day‚Äôs last act is cast in flickering gold. I‚Äôll watch the flame bob and let my mind wander, until I realize I‚Äôm sleepy. After a while, I‚Äôll lean over and blow it out, ready now for darkness ‚ÄĒ where renewal begins.

Tags: Candle Hour, Julia Scott, Letter of Recommendation, New York Times Magazine, Queben ice storm

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

© 2025 Julia Scott.