Posts Tagged ‘The California Report’

Shut In Together: 119 Neighbors and Me in an Oakland Condo

Wednesday, April 30th, 2025

I have a confession. I don’t know most of my neighbors. I don’t even know the names of everyone on my floor. I live in a tall condo building in Oakland, with a towering view of Piedmont and the surrounding neighborhoods. It’s the kind of building where you can nod to a neighbor for years, without thinking about the interaction.

No more. Because right now, almost all of us are home together. Thinking about, or trying not to think about, the virus. Our lives intersect in new ways. Our interactions will follow suit.

COVID-19 has transformed my world. My one-bedroom is now my office, tiny gym and portal to the friends I miss hugging and to my parents, who are holed up in the North Bay and haven’t set foot outside since shelter-in-place orders took effect.

In recent days, I‚Äôve struggled with my emotions and video chatted with my therapist. I‚Äôve had good days when I am overwhelmed with gladness to be part of a team at KQED whose coverage of this pandemic, deemed an ‚Äúessential service,‚ÄĚ has become more essential than ever.

I’m not the only one in my building who’s struggling to find our way in a new landscape with no view of the horizon. The coronavirus is an unspoken part of every interaction. And the fear is there, too. We fear getting each other sick, and we fear what might happen to us if we were to fall ill. My 119-unit building has about 180 residents. For the next few weeks or months, we’ll almost all be living and working here in our little units, separated by a concrete wall and under one roof. I started wondering: How are we all coping so far?

Our ‚ÄėLand-Based Cruise Ship‚Äô

I put up a note on the bulletin board in the mail room, asking my neighbors to reach out and tell me their stories. The first one who did was Gina Belleci, who lives on the sixth floor. She and her girlfriend, Jessica Holt, have been sheltering together since Gina’s startup sent everyone home. She now telecommutes from a small table wedged next to the kitchen, while Jessica works with her laptop propped up on a dresser in the bedroom.

Gina says some of her days are spent in ‚Äúsilent panic‚ÄĚ mode. Other times, she feels optimistic. Gina and Jessica take care of their neighbors. Lately they’ve been handing out toilet paper and grocery shopping for an elderly friend on the eighth floor, who really should not leave the building.

‚ÄúI think we just really need to band together. And these small, tiny ways really add up,‚ÄĚ said Gina. ‚ÄĚIt’s generosity breeds generosity. I feel really excited to be part of this building to see what happens here.‚ÄĚ

Jessica is a freelance theater director, and she told me that her prospects have become extremely uncertain, very quickly. All of her upcoming theater productions have been canceled, and the same is true industry-wide.

‚ÄúThis is all I’ve really practiced as a trade, as a craft, my entire life,‚ÄĚ she told me. ‚ÄúI’m not going to lie ‚ÄĒ the other night, I sort of threw myself into a little heap. And I and I keep saying, well, we’re going to get through this. There will come a time when we return to normal. But will we? Will we ever be able to return to normal? I don’t know.‚ÄĚ

They told me that they’ve made the difficult decision to leave. Gina’s 74-year-old mother lives in Antioch and doesn’t have anyone to take care of her. They worry that the longer they spend in a building with 180-odd people, the likelier they are to pick up the coronavirus and bring it back to Gina’s mother.

‚ÄúI either need to choose being with her, to be able to go get things for her just to keep her in the house, or we need to really commit to this land-based cruise ship we live on ‚ÄĒ which is so big and has so many people coming in and out,‚ÄĚ said Gina.

So they’ve packed their suitcases for a month and said goodbye to their neighbors.

She’s right about the sanitation issue. Our building’s maintenance man has gone home, and there is no cleaning regime, which I suspect is true of many large apartment buildings here in the Bay Area.

In a building like mine, where space is limited, it’s nice to be able to open your door and have a conversation with someone you meet by the elevators or in the mailroom. But each of those touch points now could be vectors for infection. Elevator buttons. Door knobs. I’ve taken to wearing gloves just to go downstairs or when I’m in the laundry room. When people see you inside an elevator they’re waiting for, they give a tight smile and wait for the next one. Even the mailroom has started to feel a little snug. People don’t linger to enjoy those conversations anymore.

So it was a pleasure to receive a text from my neighbor Dina Mackin on the third floor. ‚ÄúWant to meet up on the roof to see the sunset?‚ÄĚ it read.

Dina Mackin.

When I got there, Dina had a glass of ros√© in her hand and was standing in front of a darkening view of West Oakland and in the distance, the Golden Gate Bridge. ‚ÄúThis is what I have to do every day to keep my sanity,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúThe beauty of just seeing something so simple that happens every single day, that marks the passing of time. You just appreciate it more and more. And this is the time to appreciate it.‚ÄĚ

As she spoke, I realized that I hadn’t been outside in two days. This was the first time I’d tasted fresh air. When days start to run together, watching the sunset is an important form of closure. Even better to watch it with a neighbor.

Dina agreed. ‚ÄúThis is one of the few things we’re still able to do,‚ÄĚ she said.

On the Front Lines

Katie Stephenson, my neighbor on the second floor, cannot shelter in place because she is a second-year pediatrics resident at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center. I barely see her as she darts in and out to shower, sleep and drink some coffee before heading back out to the hospital for another 12-hour shift.

I spoke to her on an evening she had just tested negative for COVID-19. She had a post-allergy season cough so her doctor sent her to have a test. But she assumes that it’s only a matter of time before she does get the coronavirus, so she’s careful to limit her contacts within the building.

‚ÄúMy mission is just to keep my germs confined to my little space and not let them get out,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúBut I also think that if I’m one of the people who gets COVID-19, that I would do fine ‚ÄĒ most people my age, if we‚Äôre healthy, we do fine. I think a lot of people in my residency program, myself included, are very likely to get it and are very likely to do fine.‚ÄĚ

Katie has been on the pediatrics ward for the past three weeks. She sees children who have been admitted because their parents are afraid they might have COVID-19. All medical staff must wear personal protective equipment ‚ÄĒ essentially hazmat suits ‚ÄĒ and masks around the children, which is profoundly unsettling.

‚ÄúThere are nurses wearing the suits, and there’s multiple doctors coming in wearing the suits. It‚Äôs scary,‚ÄĚ she said. She tries to defuse the fear by making her young patients smile. ‚ÄúI have some stickers that my mom sent for St. Patrick’s Day. They’re all green. And so I have been bringing in stickers and putting them on my suit. Or I‚Äôll draw like a smiley face, to be a big yellow smiley-face person.‚ÄĚ

Katie‚Äôs supervisor has told her group that they‚Äôre running a marathon, and so far they‚Äôve only run half a mile. They need to remember to pace themselves. Luckily, Katie is an actual marathon runner ‚ÄĒ she‚Äôs done three of them ‚ÄĒ so she knows when to push herself. Her freezer is stuffed with homemade dinners prepared by her mother ‚ÄĒ a source of comfort at the end of another long day.

My neighbor Alexa Eurich is also running a marathon of sorts. Somehow, she’s had to find a way to teach her combined classroom of kindergarten and first grade students from her apartment on the fourth floor. Eurich has taught at Aurora School in Oakland for 15 years. The school closed down so quickly that no one had time to grab enough teaching supplies for a month, let alone the rest of the school year.

‚ÄúWhen you hear about teaching kindergarten remotely, you just have to laugh … because how is that even humanly possible?‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúIt’s been very hard not knowing, because I’ve felt competent at my job for a very long time.‚ÄĚ

Alexa has 16 kids in her classroom. She manages to video chat with four of them each day, in addition to checking in regularly with teachers and parents. She’s trying to keep up with the lessons her kids were learning two weeks ago, but she has to improvise with whatever books the students have around the house. They have to be trained to talk to her through a computer screen. It can be hard to connect.

‚ÄúI know without a doubt that the best way we humans learn is through a relationship. And not being with them physically when they’re at this developmental stage is very trying to the relationship,‚ÄĚ she said.

It’s also been trying for her. Because she is in remote meetings all day, her husband has to stay in the bedroom for hours at a time.

‚ÄúI’ve been working from, like, six o’clock in the morning to about six o’clock at night,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúAnd I am still in love with teaching. I love my job. But I’m not in love with this job right now. I have to learn how to do it in a way that feels wrong to me.‚ÄĚ

Staying Sane Inside Four Walls

I asked my neighbors what they are doing to stay sane amid deeply uncertain circumstances. My neighbor Guillaume Chartier and his husband Grant Eshoo have been baking lemon meringue pie and watching ‚ÄúStar Trek: The Next Generation‚ÄĚ after they have finished the day‚Äôs work at their improvised desks in the living room. (Guillaume is an animator, and Grant works for Alameda County).

They chose to re-watch Star Trek for its nostalgia, but are finding that it holds surprising relevance to our present moment on Earth.

‚ÄúThere was an episode where they were facing a lethal epidemic and they had to take measures to contain it,‚ÄĚ said Guillaume. Of course, they succeeded ‚ÄĒ thanks to Dr. Beverly Crusher.

‚ÄúIt displays a very earnest, optimistic outlook on humankind. And we’re just the kind of nerds that we enjoy watching it together,‚ÄĚ he added with a laugh. ‚ÄúIt’s all imaginary settings, but it touches on very current real human conditions and phenomena.‚ÄĚ

My second-floor neighbor Judith Rosenberg is in her mid-70s. She reckons she now spends 90% of her time indoors, except for a brisk daily walk or to pick up groceries. She escapes into serial mysteries and spy novels by authors like John le Carr√© and Charles Cumming. She also emails with her friends, which alleviates some of the ‚Äúoverriding sadness‚ÄĚ she has started to feel.

‚ÄúI have felt depression in my life. I‚Äôve felt all sorts of emotions, but I don’t get sad very much. This is a deep sadness,‚ÄĚ she said.

Her other great comfort is music. Judy has a gleaming concert piano in her apartment. Her specialty is musical improvisation.

‚ÄúI feel a certain life force when I‚Äôm playing,‚ÄĚ she told me. ‚ÄúWhen I sit down to play, there’s something about that experience that makes me feel more alive in a way. And it is a great gift.‚ÄĚ

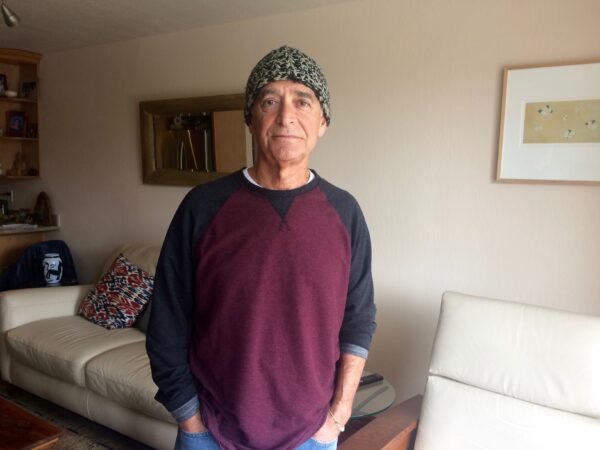

Ernesto Victoria at home. (Julia Scott)

My third-floor neighbor Ernesto Victoria is also in his 70s. He isn’t much of a worrier, but he did get concerned a few weeks ago when he developed a cough. His doctor assessed his symptoms and ruled out the coronavirus. Still, the cough has been hard to shake.

‚ÄúI get a little scared from time to time, I have to be honest with you,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúThe other day, the symptoms were really bothering me. And I just got really emotional.‚ÄĚ

He pulled out his computer and started writing memories of his childhood in Mexico and of growing up with his seven siblings.

‚ÄúMaybe there was this thought, you know, of, ‘If I die, I want my daughters to see this,‚Äô ‚ÄĚ he laughed. ‚ÄúI was just feeling sentimental and emotional.‚ÄĚ

Ernesto loves swimming, biking and hiking. With his pool closed and his favorite biking and hiking trails off limits, his daily pleasures include video chats with faraway friends.

‚ÄúIt is so good to see a face and to talk. It’s the joy of talking with somebody after being sequestered for so long,‚ÄĚ he said.

A lot of nice little things have happened in my building over the past two weeks. I was happy when Ernesto accepted my offer to shop for him sometime soon. Someone on the third floor left a message on the bulletin board offering to help anyone who needs it. Another neighbor organized the entire seventh floor into a group text, so that when someone’s leaving for a grocery run, they can take requests and minimize the number of trips from the building.

I know this virus will escalate in the next few weeks. The news will get scarier. But I’ve met more neighbors in the last week than I’ve gotten to know in the past five years. I already feel better knowing I have so many people to talk to who are facing the same situation, the same questions, as I am. We may all be behind our doors for now, but we really are in this together.

Tags: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Julia Scott, KQED, shelter-in-place, The California Report

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work | No Comments »

Beyond #MeToo: Teaching Boys About Consent

Wednesday, January 24th, 2018

Coaching Boys Into Men

When is the right time to start teaching young boys about consent, boundaries and respect toward women?

A nationwide program called Coaching Boys Into Men trains school coaches to work with boys as young as 11, who are on their school’s athletic teams. Boys trust their coaches, and the conversations that ensue are designed to plant seeds that will help prevent abuse — and give young men the tools to speak up when they see something that’s not right.

Student athletes are often the leaders at their schools, and they can set the tone for the other students.

At Petaluma Junior High School, former student Danny Marzo and Athletic Director Zach Dee told us about how the program has led to changes on a personal level in the school culture overall.

This story was part of a series on KQED’s The¬†California¬†Report, Beyond #MeToo: Sex, Abuse and Power Through a California Lens .

Tags: #MeToo, Julia Scott, KQED, The California Report

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

© 2026 Julia Scott.